Finest Hour 121

Cover Story – Queens of the Seas

April 17, 2015

Finest Hour 121, Winter 2003-04

By Winston S Churchill

Page 23

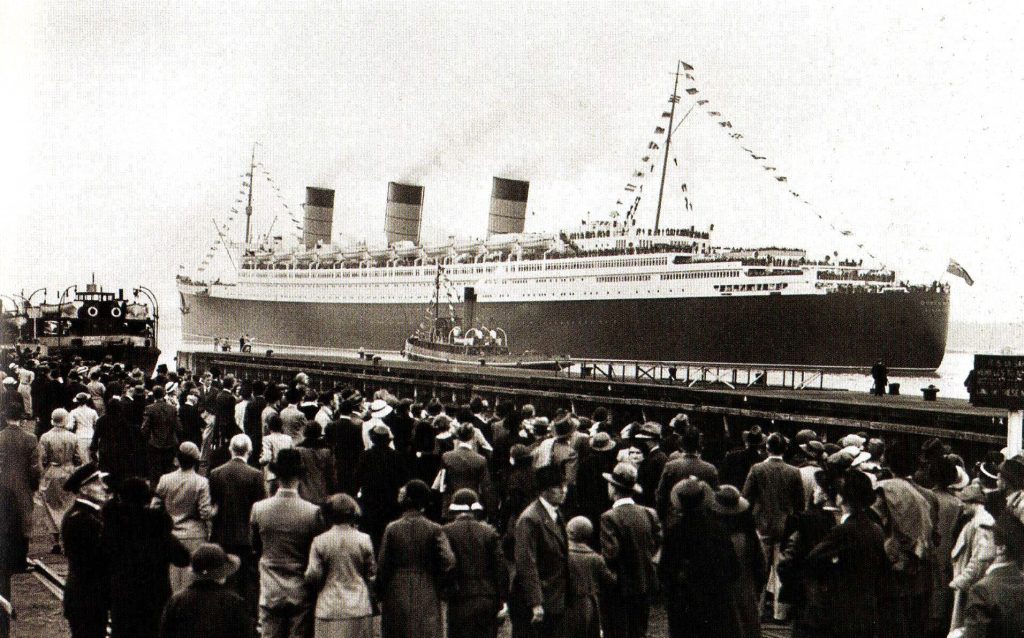

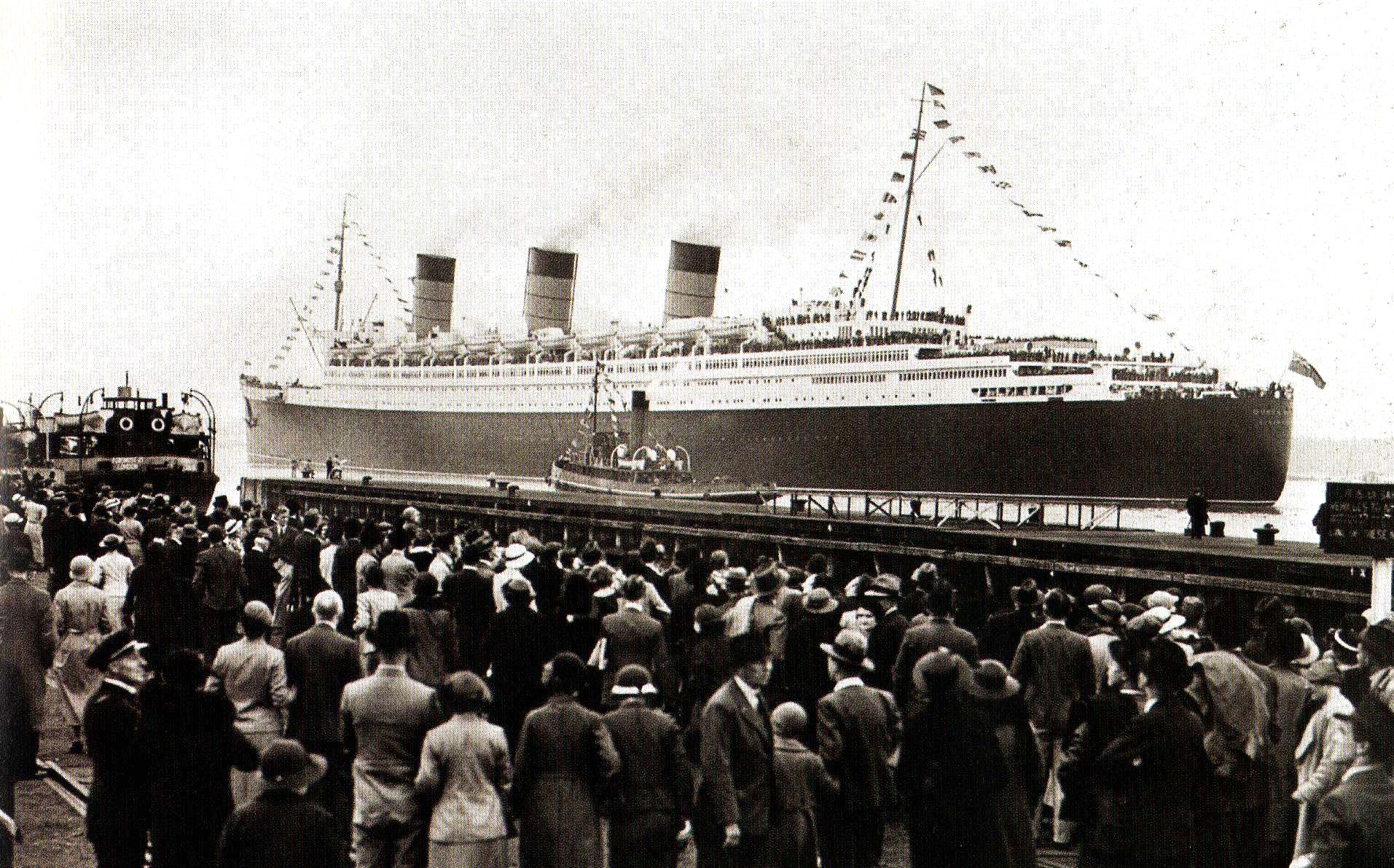

‘Queen Mary’ leaves Southampton, UK, on her maiden voyage to New York, USA – 27 May 1936The building of the Queen Mary represents the decision of Great Britain to regain the Blue Ribbon of the Atlantic passenger service. This decision has been long delayed and many circumstances most vexatious to British minds have obstructed it.

‘Queen Mary’ leaves Southampton, UK, on her maiden voyage to New York, USA – 27 May 1936The building of the Queen Mary represents the decision of Great Britain to regain the Blue Ribbon of the Atlantic passenger service. This decision has been long delayed and many circumstances most vexatious to British minds have obstructed it.

After the Great War was over, as part of the conditions of peace, Germany was obliged to yield up her transatlantic liners in replacement of the far greater volume of tonnage sunk by the U-boats. We therefore received the two prewar German liners, Imperator and Bismarck, which were renamed respectively the Berengaria and Majestic. These vessels had been built as long ago as 1912. They belonged to the epoch before men’s minds had been stretched by the terrible convulsions of the war. They were magnificent ships, the equals in many respects of their contemporaries, the Mauretania, Lusitania and Aquitania. But the possibilities of science, the modern ideas of comfort, convenience and luxury, rendered it possible to design and construct after the war vessels which were finer and faster.

Great tales have been told of the cruel hardships inflicted upon the Germans by the war indemnities exacted from them under the Peace Treaty. They proved in the end to be the gainers from every point of view. Out of the large sums of money which die Germans borrowed from America and Britain, tliey were able to build in 1929 two great ships, the Europa and Bremen, which were the last word in magnificence, luxury and modernity, and which eclipsed all rivals by three or four knots speed. Germany thus re-entered upon die transadantic passenger trade in the most favourable circumstances, competing with her own old ships, now in British hands, with brand-new vessels built on money borrowed from the Allies! Great Britain, weighed down with debt, smitten by the economic blizzard, and disappointed in German repayment, found herself unable to put contemporary vessels in the water to meet this new challenge.

2024 International Churchill Conference

There for a time the matter rested in a most lamentable plight. Meanwhile other countries, particularly Italy, built great and splendid ships of die very latest type. Since the Aquitania was built no transadantic liner of the first order had been laid down in British yards. Nearly a quarter of a century passed without any opportunity being given to our designers to construct the mammoth vessels, in the light of the knowledge of new tastes and requirements of the travelling public, which have developed since tlien. The glory of the Aquitania and Mauretania is diat they have, for all this period, been able to make head against the tremendous State-aided competition of ships very much younger than themselves. It is from this fact that we may draw good hopes for the future.

In all questions of re-equipment on a large scale, whoever can afford to wait till the last has the opportunity of going from the bottom to the top of the class. Such was the position when Great Britain began to recover from the world slump of 1930 and 1931. The ordered and orthodox system of our finances enabled both public and private enterprise to look forward to a new and successful effort to reestablish our industrial and maritime supremacy. The decision to build the Queen Mary, which must of course carry with it the building of a sister ship, was the result of this revival. Her launch by Her Majesty Queen Mary in 1934 was an occasion of national rejoicing. Her entry into the transatlantic passenger service signalized and symbolized the resolve of British industry and the British nation to assert their long-undisputed preeminence on blue water and to be worthy of their old and sure renown.

It is, however, very necessary to understand the conditions which must govern the carrying through of this brilliant and spacious enterprise. The history of the British transatlantic passenger service is not a series of “stunt ships” giving satisfaction only to megalomania and record-breaking or ostentation. The policy underlying the construction of the Queen Mary is a sober tale. For every trade route in the world, from the North Atlantic service to the coastal service, there is at any given time a ship of exactly the right size and exactly the right speed. As naval architecture and marine engineering progress, that right size and right speed tend to increase on the majority of routes, especially on the North Atlantic, where there is no check on conditions at ports of call or en route. The depth of water in the Suez Canal imposes definite limitations on the development of our Oriental lines. But New York, Southampton and Liverpool enable the largest vessels ever built by man to be planned and operated. History records that during its ninety-six years’ existence in the so-called Atlantic ferry, the Cunard Company has always succeeded in placing in service ships of the right size and right speed for the work they were required to do.

The first Cunarder, the paddle-steamer Britannia, was but 207 feet in length with a gross tonnage of 1,154 tons. In 1840 this ship inaugurated the first regular steamship, mail and passenger service across the North Atlantic. She was exactly suited to the service of her day; that is to say, in seaworthiness, safety, comfort and speed she formed the highest harmony of economic relations for which the public of those times was prepared and able to pay. The Umbria and Etruria in 1884, the Campania and Lucania in 1893, and the Lusitania and Mauretania in 1907, each in their turn, carried out this new principle. When they were commissioned they embodied the latest developments of naval architecture and marine engineering. They were especially designed for the service for which they were intended, and they were an immediate success both scientifically and financially. Indeed, the Lusitania and Mauretania were in many respects ahead of their time, and the latter held the Blue Ribbon of the Atlantic for nearly twenty-two years.

It would none the less be wrong to suggest that the laying down of the Queen Mary is the reply to the German Europa and Bremen. The aim of the builders of the Queen Mary has not been a reply to any particular ship, but rather the designing of a vessel which would meet the exact conditions, natural and financial, upon which a sound and sure policy would be based. For four years before the Queen Mary was ordered in 1930, the whole problem was considered from every possible angle.

For the first time in the history of Atlantic travel it was found possible, owing to the amazing developments in naval architecture and marine engineering, for two vessels of sufficient size and speed to maintain a regular weekly service between Southampton, Cherbourg and New York. This had hitherto been maintained by three ships. If it could be achieved by two, it was evident that large economies in the cost of the services could be secured, which could be distributed between the shareholders in the Company and the travelling public. The speed of the Queen Mary, and her contemplated sister ship, is not designed for mere record-breaking. It is dictated by the time necessary for her to perform the journey regularly at all seasons of the year, so as to give the number of hours required in port on both sides of the ocean. Size has been dictated by the necessity for providing sufficient passenger accommodation to make a two-ship service pay.

The Queen Mary and her sister ship have not sought to be the largest and fastest which can be constructed. That would have been comparatively easy. Although in fact they will be the largest and fastest in the world, they are at the same time the smallest and slowest which could fulfill the necessary conditions for accomplishing a regular two-ship service. They are as inevitable to the Atlantic ferry as was their predecessor Britannia ninety-six years ago.

Almost any fool can build a ship at a loss. The Queen Mary is designed, naturally and properly, to make a profit for her owners. But it is impossible to disassociate the larger questions of national aspirations and national prestige from an enterprise of this kind. To Great Britain, the centre of Empire and world-wide commerce, the pioneer of modern manufacturing industry, shipping is a symbol of strength and security. We are proud—and justly proud—of our long record of achievement as seafarers and shipbuilders. To a great extent we judge ourselves, and we are judged by others, by our ships. It is especially on the North Atlantic that shipping and shipbuilding reputations are made or lost. That is why the general public attaches so much importance to the purely mythical Blue Ribbon of the Atlantic. It is an assurance that all is well in many vital departments of the national economy. To hold the Blue Ribbon is a triumph at once of naval architecture, of marine engineering, of shipbuilding technique, and of shipping management and control.

These are factors which it is impossible to ignore. And there is a real commercial advantage in the capture of this coveted distinction. North Atlantic history has proved time and again that it is the finest ship in the trade which gets the cream of the traffic, not only for the operating company but also for its country.

Figures prove this conclusively. In the year 1931 the German liners Bremen and Europa, joint holders of the Blue Ribbon of the Atlantic, carried between them a total of 85,548 passengers, as compared with the aggregate of 35,400 of their two British competitors, Aquitania and Berengaria.

There are certain other considerations which have made the Queen Mary and her contemplated sister ship necessary. They will carry mail as well as passengers. In modern business the element of time is of paramount importance, and those who have commercial correspondence to send across the Atlantic are anxious to dispatch it at once by the fastest ships. So in recent years we have witnessed the sorry spectacle of foreign-owned express liners carrying British mails to New York because no fast British mail liner was making the crossing at the time.

Equally or perhaps more important is the fact that the character of transatlantic passenger traffic has changed in a very radical way. Before the war, there poured across the North Atlantic a steady stream of emigrants seeking fortune, or at least work, in the New World. The United States was the Golden Land of Opportunity to millions of poor people throughout Europe. They looked wistfully across three thousand miles of ocean and dreamed of the day when they would be able to join the relatives or friends who were already making good under the Stars and Stripes. Today emigration has practically ceased. It has been killed by the quota system. In place of the emigrants is the great army of tourists. Pleasure, change, adventure, rather than work or wealth, are the magnets that draw an increasingly large number of men and women across the dividing sea.

This is an age of travel. There are countless thousands to whom a holiday means not merely rest from labour, not merely an opportunity of recreation, but a chance to gain new experiences and taste unfamiliar modes of life under foreign skies. For a time the Continent satisfied this hunger for change, but more recently the holiday adventurers have been going farther afield. The tourists have discovered America.

To the already huge army of Atlantic holidaymakers the Queen Mary will add new thousands. She has catered for them specially. Her passenger accommodation, or a large part of it, is expressly designed to attract this class of traveller. This again is an inevitable development. It was necessary that a ship should be built which would take into account more fully than ever before the needs of the tourist, essentially different from those of the emigrant. To the latter, the voyage was a necessity, and though as a rule he travelled comfortably enough, he was apt to attach more importance to cheapness. To the tourist, the sea trip is part of the fun. He is prepared to pay more than the emigrant, but he has a far higher standard of comfort. And he demands much more in the way of facilities for sport and amusements. He will get all these things in the Queen Mary.

She is also the first British ship to bring a holiday in America within the reach of the millions of men and women who have only a fortnight off duty. By leaving Southampton on one Wednesday and returning from New York the next she makes it possible for passengers doing the round trip to return home within fourteen days.

This is a sound business proposition. But again it is something more. I can imagine no surer way of cementing Anglo-American friendship than exchange of holiday visits by people of both nations. In the past many more Americans have spent vacations in “the Old Country” than Englishmen have crossed to America for pleasure. The balance is now being righted and the Queen Mary will enable the rectification to proceed more rapidly. In that I see a very great advantage to both the United States and ourselves.

The other day I visited the Queen Mary. I talked to the men who were preparing her for her maiden voyage and to some of those who will sail her across the Atlantic. I was shown the marvels of the great ship. I walked for miles upon miles exploring her. But there was so much to be seen and of so absorbing an interest that it was only after I had said “good-bye” and started on the homeward journey that I became conscious of fatigue.

One of the things that particularly impressed me was the gracefulness of her lines. To me a ship is a beautiful thing and the Queen Mary challenges comparison with any vessel I have seen. She gives an impression of strength, power, and speed that is unforgettable.

The hull, I was told, is the result of over 7,000 experiments with a variety of models, which Messrs. John Brown & Co Ltd., the shipbuilders, carried out in their experimental tank at Clydebank before the work of construction started. In this tank every possible type of Atlantic weather can be—and was —reproduced, and the models travelled, in all, over a thousand miles in order that their seaworthiness and performance in every conceivable set of circumstances should be noted and compared.

The length on the waterline of the great ship is 1,004 feet; the beam is 118 feet. From keel to top superstructure her height is 135 feet; from keel to top forward funnel, 80 feet; and from keel to masthead, 234 feet.

I was shown a number of pictures, drawn accurately to scale, which give a vivid idea of the Queen Mary’s size. One of them shows what would happen if the liner were set down in Trafalgar Square. The Nelson Column is on her starboard beam, the crown of the Admiral’s hat reaches to about the boat deck. Her stern has pushed in the walls of the Garrick Theatre in Charing Cross Road; her port side just fits alongside St. Martin-in-the-Fields and South Africa House; the National Gallery has sustained serious damage and the liner’s stem protrudes into Whitehall.

Another of these pictures shows the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbour drawn against the background of the Queen Mary. The upraised hand of the famous figure, which has typified America for so long in so many millions of minds, comes to just above the bridge. The towers of Westminster Abbey do not reach to the top of the mainmast. There is a promenade deck that is twice as long as the facade of Buckingham Palace. The head of Sphinx is well below the main deck at the stern. And if the Queen Mary were stood on end alongside the Eiffel Tower in Paris, she would overtop it by nearly twenty feet.

Everything that ingenuity can devise is being done to ensure the comfort of passengers. The three large funnels will be raked in such a way as to ensure freedom from funnel gases on the promenades of the upper decks. The public rooms are unusually large. It would be possible, for instance, to put nine double-decked passenger buses in one lounge and then to place three Royal Scot locomotives on top of them. An area of nearly two acres will be available for promenading and deck games.

I like the way in which the tourist-class passengers have been provided for. From time to time the Queen Mary has been referred to in the Press and elsewhere as a “luxury” ship. If the term is used to suggest unnecessary and useless extravagance, it is entirely inaccurate and misleading. But it is a “luxury” ship in the sense that the passenger accommodation includes every modern improvement likely to attract and please the traveller. The standard of comfort in the modern home is higher today than ever before. Compared with prewar standards, it might well be called luxurious. It is only natural, therefore, that the Queen Mary should offer her passengers far more than ships which were built before this general advance in the art of living; that it should, in this as in other respects, set a new standard in the world of shipping. Yet actually the decoration of the passenger accommodation represents only a very small percentage of the total cost of the liner.

Never in the whole history of Atlantic travel has so lavish provision been made for those who travel “tourist.” Their stateroom accommodation extends over five decks. Each stateroom is being supplied with hot and cold water and has its own individual ventilation system, which passengers will be able to control for themselves. The main tourist lounge will have a parquet dance floor, and there will be a cinema for those who cannot imagine a holiday without films. But I think the features which will appeal most of all are the amazing amount of deck space allowed for outdoor exercise and recreation and the large indoor swimming-pool and gymnasium. All these are exclusively for the use of tourist passengers. But even the third-class accommodation, which again includes a film theatre, is planned on spacious lines and constitutes a veritable revolution in the standards for this class of travel.

If I have devoted so much space to this aspect of the Queen Mary, it is because, to my mind, it is of very real importance. The man of wealth has always been catered for by the great liners, as he is in the Queen Mary, but here we have a recognition of the development of the travel habit among ordinary men and women, with all that this implies for international understanding and friendship in the future. It is a recognition that travelling for pleasure—and travelling that is pleasure—must be brought within the financial reach of those who, with only a limited amount to spend, want to get the most and the best for their outlay. It means, very definitely, an enlargement of the possibilities of life to a very great number of people that would have been impossible—undreamt of—even a few years ago.

In going over the ship, I thought of these people, the future passengers of the Queen Mary, to whom she will open new vistas. But I thought also of the many thousands of others, some of whom may never even see the ship, but to whom she has already meant the dawning of better days.

The contract for the construction of the vessel came at a time when the shipbuilding industry was in a distressed state. The building of the Queen Mary has ensured that the art of constructing great liners shall not be lost. It has involved the employment, among others, of large numbers of apprentices, who have thus had the opportunity of learning a trade and craft peculiarly British and for which, I hope, brighter times now lie ahead.

Actually, about 7,000 men have been working on the Queen Mary in John Brown’s shipyard. What that work has meant to many of them in the rebirth of hope and the renewal of self-respect is beyond computation. And behind the 7,000 there looms the great multitude of those who have contributed in other ways to the building of the vessel.

The Queen Mary is an epitome of Britain. There is hardly an industry in the country which cannot claim to have some share in her. This great enterprise has meant the placing of orders with nearly two hundred firms in Great Britain and Northern Ireland; it has given employment, in one way or another, to approximately a quarter of a million people. Under the smoky skies of the Potteries workmen have moulded 200,000 pieces of china and glassware for her equipment. The skilled artisans of Sheffield have fashioned her cutlery. In London, in Cheltenham, in Bath and in Glasgow craftsmen have put heart and soul into the work of making furniture that carries on, in our modern times, the traditions of Chippendale and Sheraton. Northern Ireland, Lancashire and Yorkshire have seen their looms busy with the manufacture of linens and woollens of the finest qualities. From Darlington have come the stern frame and rudder—the latter the largest ever constructed for any ship. It weighs over 140 tons, and the job of hoisting it into position involved many days of intricate work. London, Rugby and Manchester united to supply the electrical equipment, with its 4,000 miles of cable and 30,000 lamps. The great anchor came from Staffordshire.

So one could go on. All over the country men and women have been giving of their best to the Queen Mary, with the result that when she is commissioned she will be a floating British Industries Fair, displaying to the cosmopolitan world that will travel in her not only the marvels of British shipbuilding and marine engineering, but a widely representative selection of the products of British industry and British craftsmanship at their highest.

And even beyond the borders of Britain there are those who have given to the Queen Mary and benefited by her building. The Empire’s forests—the world’s forests, indeed—have been searched for the fifty-six varieties of beautiful woods used in the decorative schemes.

Of one thing I am sure after my tour of the ship. All those who have, in whatever way, contributed to her may be proud of the work they have done. The Queen Mary stands in my mind as a conquering symbol of British enterprise, finely conceived, nobly planned, and magnificently carried out.

She is to sail from Southampton on her maiden voyage on 27 May. The wishes of the whole country will go with her across the Atlantic; the eyes of the whole world will be upon her. She is a Cunard White Star liner, latest of a long line of splendid vessels, but she is also OUR ship, the symbol of our renaissance, of the new hope and the new vigour that have at last overcome the weariness of the postwar years and set our feet on the old high paths once more.

Greatest of all the pathways for Britain is the sea—the sea that has been our highway to Empire and to wealth, and across which we draw, from the four corners of the world, the daily bread by which we live. And once more, as the Queen Mary sets out, we feel confirmed in our ancient dominion over the wide waters—that dominion of whose peaceful purposes she is again a symbol. May she win back the Blue Ribbon that the Mauretania held for over a score of years—and may she retain it against all comers as long as did her great predecessor.

Good luck to her—and to all who have had a hand in her making, and to all who will sail in her.

“Queen of the Seas” was published in The Strand Magazine for May 1936 (Woods C299) and reprinted in The Collected Essays of Sir Winston Churchill: Churchill at Large (ICS A145), London, 1975. It is published here, for only the second time in article form, by kind permission of the Churchill Literary Estate and Winston S. Churchill.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.