Finest Hour 162

Inside the Journals

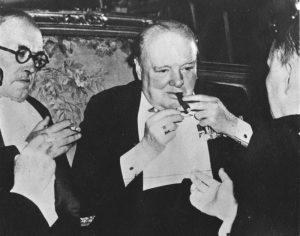

Winston Churchill, Parliament Square, London © Sue Lowry & Magellan PR

February 18, 2015

Finest Hour 162, Spring 2014

Page 45

Abstracts by Antoine Capet

GERMANY AND DISARMAMENT BETWEEN THE WARS

“British Conservative Opinion and the Problem of Germany after the First World War,” by Greg S. Parsons, International History Review 35/4 (2013) : 863-83.

This work examines British Tory attitudes towards the Weimar Republic through the lens of several issues from the 1918 Armistice to the 1923 Ruhr Crisis. A curious feature of British Conservative opinion at that time was its consistent hostility towards the new democratic German state. To be sure, Britain had fought a long and costly war with Germany, and passions had not cooled. Though from late 1918, the German government was committed to democratic principles Britain claimed to favour, many Tories doubted that the change was genuine or stable. During its formative years the Weimar Republic faced challenges that would have tested any nation. Political and economic conditions within Germany undermined the new government’s prospects; yet many Tories refused to consider these challenges. Ironically, the attitudes of British Conservatives added to the difficulties Weimar Germany faced in dealing with the postwar world.

“The Thin End of the Wedge: The British Foreign Office, the West Indies and Avoiding the Destroyers-Bases Deal, 1938-1940,” by Charlie Whitham. Journal of Transatlantic Studies 11/3 (2013): 234-48.

2024 International Churchill Conference

The Destroyers-for-Bases agreement of September 1940 was a milestone in establishing the Anglo-American relationship, but is best understood in the context of British policy towards the West Indies that developed in response to initiatives from the U.S. well before the agreement. Beginning in 1938, the British Foreign Office used West Indian colonies as bargaining counters to win American friendship—but also to avoid or at least control creeping American influence over these possessions. This perspective better explains the policy context of the Destroyer-Bases deal, which signalled not only a turning point in the war but also of British attitudes towards its Empire in the face of mounting American power.

Note: Reffering to this subject in FH 160, Prof. Warren Kimball offers a note by Ph.D. student Colin Williamson, Ohio State University: “The Destroyers for Bases deal of September 1940, ostensibly designed to reinforce the Royal Navy’s operational strength with fifty older American destroyers, ultimately added to the workload of the Royal Dockyards since so many of the American ships required refits before becoming operational.” (For Williamson’s citations please email the editor.)

“The Foreign Office, the World Disarmament Conference, and the French Connexion, 1932–34,” by David K. Varey, Diplomacy & Statecraft 24/3 (2013): 383-403.

The traditional interpretation of British foreign policy during the Geneva Conference for the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments casts Britain as an honest broker, striving to bring France and Germany together in a bid to square their differences over security and equality. But from the Foreign Office perspective, Britain played broker between the former World War I allied powers and Germany on the other.

This activity had two particular strands. The Foreign Office wanted first to secure French support for any disarmament programme before seeking German support; and second to circumscribe German military potential where possible.

This is a new interpretation of the Foreign Office’s role and aims. Arguably, in 1932-34, Churchill did not want Britain to act as an “honest broker” between France and Germany, but to side resolutely with France.

“The Ghosts of Appeasement: Britain and the Legacy of the Munich Agreement,” by R. Gerald Hughes, Journal of Contemporary History 48/4 (2013): 688-716.

This article on British foreign policy during and after the Second World War argues that an unapologetic attitude to the past by the British Foreign Office often entailed the adoption of evasive legal formulae. Thus, while the German Federal Republic and Czechoslovakia achieved a modus vivendi over the events of 1938 by 1973, the British refused to repudiate Munich ab initio, and applauded the West German decision to do the same. London steadfastly maintained this position until 1992, when the Cold War ended and Czechoslovakia rejoined the ranks of democratic nations.

This article explores the reasoning behind the British policy, While historians frequently discussed the “shame” of Munich, British policymakers rarely expressed guilt, seeking instead a benign view of the Munich agreement. Furthermore, many of the actions of the British government during the Second World War, not least with regard to the Katyn massacres and at the Yalta Conference, reinforced the idea that Munich had been a creature of its time, a “necessary evil.” (See Munich articles this issue, pages 12-31.)

Drawing extensively on primary sources, this is a contribution to the historiography of British foreign relations and that of collective institutional memory and appeasement.

Professor Capet is head of British Studies at the University of Rouen, France.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.