Finest Hour 166

As Others Saw Him: Encounters with Churchill

July 24, 2015

Finest Hour 166, Winter 2015

Page 32

By DANA COOK

“There can be no doubt that there was a certain grandeur about the old man”—Auberon Waugh, 1976

2024 International Churchill Conference

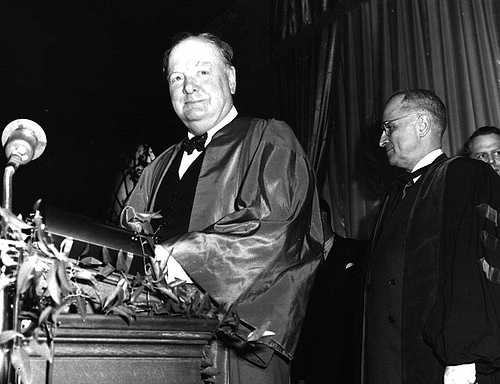

Churchill prepares to speak at Westminster College, 1946Toronto, 1932: Words Lost in a Cavern

Churchill prepares to speak at Westminster College, 1946Toronto, 1932: Words Lost in a Cavern

Foster Hewitt, hockey broadcaster

Most of the celebrities with whom I came in contact were friendly and cooperative. The individual who gave me the most trouble was not a star of stage and screen, he was a statesman and warrior—Winston Churchill. Churchill had been touring North America on a speaking tour and the itinerary included Toronto. At that time the Gardens’ acoustics were a problem but we had arranged for the speaker to use the regular stand-up type of microphone; however, when he saw it he raged in language that was later to make him famous. He emphatically protested that a microphone of that nature would just not do, and demanded a lapel mike. He had used such a type in Washington and had liked it because it gave him freedom of movement and did not tie him to one spot. However, Churchill did not appreciate that while a lapel microphone might be suitable when addressing a small auditorium audience, its effect would be lost in the cavernous Maple Leaf Gardens.

Eventually we gave in to the distinguished lecturer and arranged to get him a lapel microphone; still, for our own protection we also installed stand-up equipment so that the speaker could either wander or remain fixed. That arrangement seemed a reasonable compromise but Churchill unwisely prefaced his address by enquiring from the audience, “Can you hear me distinctly out there?” “No!” came the shouted response; whereupon the irate speaker pulled off his lapel mike, remained away from our substitute and addressed the audience in his natural voice. Unfortunately, he never reached them.

—His Own Story (Ryerson Press, 1967)

Chequers, 1941: Like a Rumpled Bed

Eric Ambler, Mystery Writer

The Prime Minister enjoyed Hollywood films…there was a roomy projection theatre upstairs at Chequers and off-duty officers from the guard company and our battery would sometimes be invited up for the weekly film shows. On Mr. Churchill’s birthday in November 1941, I was one of those who went…. We found the theatre full except for the front row. That was where the Prime Minister was sitting; we could see that from the landing outside. Over his siren suit he was wearing a vast padded and quilted dressing gown made of a beige material. Under the projection beam and in the flickering reflections from the screen he looked like a rumpled bed.

Mr. Churchill had a cigar in one hand and a brandy glass in the other. For a time, as the second projector took over from the first, I thought the film had his undivided attention. Then I became aware of an intermittent sound coming from the dressing gown. It wasn’t snoring, he wasn’t sleeping. By listening more carefully and leaning towards him slightly, I understood what I was hearing; he was rehearsing a speech. I could not distinguish the words; what he was rehearsing was the way he would deliver the words; what I could hear from the rhythms and cadences of delivery being hummed in a nasal tonic sol-fa of his own.

— An Autobiography (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1985)

Ottawa, 1941: Photo Op

Yousuf Karsh, Photographer

I waited in the Speaker’s Chamber, and presently Mr. Churchill came in, more or less on the arm of Mackenzie King and followed by his entourage. I switched on my floodlight, and Churchill ejaculated, “What’s this, what’s this?” No one had the courage to say, “We have brought you here to be photographed,” so I stepped forward and said, “Sir, I hope I will be fortunate enough to make a portrait of you worthy of this historic occasion.” He glared at me, then looked questioningly at his entourage, and said, “Why was I not told?” They started to laugh, which hardly helped matters. It was obvious they thought that the guest of the Canadian government had not been given much choice. He threw away his old cigar, lit a new one, puffed at it with a mischievous air, and said, “You may take one.” [Karsh took at least seven; see cover, FH 154.]

—In Search of Greatness (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962)

Piccadilly, 1942: Losing His Touch?

Noel Coward, Playwright

Went to the theatre [to see Blithe Spirit]. Received PM and Mrs. Churchill in box after first act. He was very amiable and in a good mood. He said the war would not last a long time and that he did not think we should have continuous air raids during the winter, just a few rovers.

Winston Churchill read “production” White Paper before the Commons. I feel that he is losing his touch. He is fine when making stirring speeches but on major issues I doubt his judgement. His prophecies just before the war, when he was a voice in the wilderness, were wonderful but he seems less good in judging strategy and men. He knows the temper of the people in crisis but I doubt if he really knows the people themselves. It may be heresy to say so, but I feel that it if he goes on playing a lone hand, refusing to listen to younger and wiser men, he will fall, and this will be said because it will damage his legend.

—The Noel Coward Diaries, edited by Graham Payn and Sheridan Morley (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1982)

Staten Island, New York 1942: Unexpected Arrival

Sid Caesar, Comedian

We [Coast Guardsmen] were all put onto huge lifeboats with motors and took off out of the canal into the harbor, all the way to a railroad pier in Hoboken, New Jersey…. At about 7:00 am from nowhere a day liner started heading toward us and a railroad train started to back up to the pier. The boat docked and the lines were secured. A company of British marines started to get off. Each of them was a big bruiser with a rifle and a fixed bayonet.

British marines, I thought. What were they doing here? Are we at war with England? The marines formed a double line from the gangplank of the ship to the train. A train car was backed up, and I saw a man wearing a homburg hat and smoking a huge cigar walk off the gangplank through the paired marines. “Holy smoke,” I thought. “It’s Winston Churchill! He’s going to Hyde Park to see Roosevelt!” Seeing Churchill was exciting, but otherwise life in the Coast Guard was routine, happily so, and monotonous.

—Caesar’s Hours: My Life in Comedy, with Love and Laughter, with Eddy Friedfeld (New York: Public Affairs, 2003)

Downing Street, 1940s: Tiger Shooting

Madame Wellington Koo, wife of Chinese diplomat

When T.V. Soong, head of the Bank of China, came to London, Churchill gave a luncheon for him….when the Prime Minister came through the gate, glowering, and approached us with his bulldog walk, a hush fell over the company. Things were no better when we sat down to eat. His bad mood conveyed itself to the rest….I began to ask about his painting and gradually he warmed and launched into a story: when he wanted to paint waves, he hired a man to sit in a boat and beat an oar in the water.

We laughed and he smiled for the first time and turned to me and said he had one thing he wanted to do before he died: shoot a Manchurian tiger. Manchurian tigers are huge, with thick fur—like bears; in Peking, we had a pelt of one hanging on a wall of our palace. I said to him that T.V. Soong could arrange a shooting expedition for him. No comment. The conversation languished again. His silence went on so long I felt miserable. Finally I pointed to a little box in front of him on the table and asked what it was. It turned out that it contained snuff. Churchill was so astonished that I had never heard of snuff that he took great delight in demonstrating how it was to be taken and telling me stories about its origin.

—No Feast Lasts Forever, with Isabella Tavers (New York: Quadrangle/Times Book Co., 1975)

Quebec, 1944: Impatient

Arnold Heeney, Diplomat

The principal members of the cabinet War Committee with their handful of senior advisers, civil and military, accompanied the Prime Minister [Mackenzie King] to Quebec [for the second of two conferences held there among Allied war leaders]. As before it had been arranged that the Canadian party would confer with the British delegation before the arrival of the President [Franklin Roosevelt]. We were to meet after lunch in the long gallery of the Citadel, which opens out to the broad platform overlooking the St. Lawrence. As the hour approached we assembled in the sunshine outside the conference room, and Churchill strolled happily up and down flanked by two of his senior officers. A few minutes before the time fixed all was in readiness. Except for one thing. King had not arrived. In some anxiety, since I was responsible for the meeting arrangements, I was watching Churchill. I saw him stop, take his watch deliberately from his waistcoat pocket and look at it. Then, raising his head, he beckoned to me. “Young man,” he pronounced solemnly, “where is your Prime Minister? We cannot” (indicating the chiefs of staff) “keep these great men waiting.” I explained that the Prime Minister had a speaking engagement at lunch time, that it was an obligation of importance, and that I felt sure he would be with us soon. Churchill grunted but seemed satisfied. A few minutes later King turned up, having just delivered to the Quebec Reform Club the speech reaffirming his opposition to overseas conscription which was so greatly to upset [J.L.] Ralston, then minister of national defence.

—The Things That Were Caesar’s: Memoirs of a Canadian Public Servant (University of Toronto Press, 1972)

Niagara Falls, 1944: Falls Still Falling

Charles Lynch, Journalist

After the conference [Quebec, 1944], Churchill went trout fishing in the wilds of Quebec and then proceeded to Niagara Falls. A few of us went there to lie in wait, and when he arrived we were told that we could approach him as he stood at the brink of the falls and that three questions would be permitted. Harold Fair was selected for the first question, since he represented Canadian Press and hence had priority. As it turned out, his one question was all that got asked.

“Mr. Churchill,” he said, “have the falls changed much since you were last here in 1904?”

The great man looked at Fair with an expression that said this was a peculiar question to put to a man who held the destiny of the world in his hands. Then, glowering, he took a long puff on his newly lighted cigar, turned ponderously toward the raging waters, gave the entire panorama a slow scan, and then returned his gaze to the questioner. “The main principle,” he intoned, “remains the same.”

—You Can’t Print THAT! Memoirs of a Political Voyeur (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1983)

Fulton, Missouri, 1946: Acting a Speech

David Brinkley, Broadcast Journalist

While I had often seen Churchill in pictures and films, I had never observed him in person. And while I had heard a few and read many of his wartime speeches I had never sat at his feet and watched him speak. And I thought at the time I was seeing more than a statesman. I was seeing an actor who did not make a speech or deliver a speech. He acted a speech. He threw his whole body into it but somehow managed to so do without excessive gestures or histrionics. The words alone were enough, his speaking style the high distilled product of a thousand years of upper-class English language and rhetoric. The audience sat still, quiet, entranced, eager to applaud but afraid to. The clapping of hands would have somehow seemed almost vulgar. Further, he was not talking to those of us in the hall. He was talking to the world.

—On Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech at Westminster College, in A Memoir (New York: Knopf, 1995)

Washington, 1946: Painting Critique

Dean Acheson, Statesman

…after Mr. Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech…my wife and I lunched with him and his daughter Sarah and Ambassador and Lady Franks at the British Embassy. My wife, who idolized Mr. Churchill, anointed him with ample flattery, which he obviously enjoyed. When the talk turned to painting and he discovered that she had seen reproductions of his work and was herself a painter, he asked for a criticism of his. In doing so he passed from a field in which he was a world master to one in which she accorded him no superiority whatever. While she liked his work, she pointed out areas where improvement was possible. This was not what he expected or wanted; she did not yield an inch. He puffed harder on his cigar and fought back. Our hostess broke up the criticism by rising. He chuckled as we walked out of the dining room, and remarked to me that the critic had plenty of spirit—a quality of which we were already aware. In 1950…the Churchills entertained us at lunch and showed the originals of the works she had criticized.

—Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department (New York: Norton, 1969)

1946: Autographed Holograph

Floyd Chalmers, Editor and Publisher

…we drove down to Hever Castle, Lord Astor’s country place in Kent, a palace out of a fairy tale [where] the guest of honour was Winston Churchill….I dared to become a pest that day, an autograph hunter. I had with me a small book, shaped like an autograph album, in which were reproduced in facsimile the holograph messages that Churchill had written [General Bernard] Montgomery on the eves of ten decisive battles. I asked Churchill to autograph it. He scowled a bit and then smiled. He would autograph my copy, he said, but would autograph nothing more that day. Later I sent the book to the War Office, where Montgomery also autographed it. It is now one of my treasures.

—Both Sides of the Street: One Man’s Life in Business and the Arts in Canada, (Toronto: Macmillan, 1983)

London, late 1950s: Beat It, Guttersnipe!

I think it must have been in White’s Club. Randolph introduced me as “this boring little creep who keeps following me around”—pure vintage Randolph, of course. Sir Winston eyed me up and down, and I’ll always remember his words: “Get out of here, you guttersnipe,” he said, “and leave my son alone.”

There can be no doubt that there was a certain grandeur about the old man although we were always on opposite sides of the fence politically.

—Auberon Waugh, Journalist. Four Crowded Years: Diaries 1972—1976, edited by N.R. Galli (London: Deutsch, 1976)

Dana Cook has published collections of literary and political encounters.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.