Finest Hour 169

Churchill’s World – Twentieth-Century Fighting Sail

November 10, 2015

Finest Hour 169, Summer 2015

Page 20

By Keith Dovkants

Keith Dovkants is the author of A Combat of Devils, a novel about Q-ships in the First World War published by Matador in 2012. The full-length version of this article originally appeared in the winter 2012 issue of The Marine Quarterly and is reprinted with kind permission.

“…some of the most brilliant and daring stratagems in the naval war.”

Winston S. Churchill, The World Crisis

2024 International Churchill Conference

Two ships of war are locked in a duel to the death. One swiftly tacks. Her guns come to bear. Her broadside hurls hot metal into her adversary’s hull….

A scene from the era of fighting sail? Indeed, but not so long ago as you might think. This action took place on the cusp of living memory, in 1917. The sailing ship was Fresh Hope, a wooden three-masted schooner commanded by Lieutenant J. Martin, an officer in the Royal Navy’s Special Service. Fresh Hope was a Q-ship, a merchant marine vessel secretly armed with guns and sent out to lure the Kaiser’s marauding U-boats into a trap. Martin scored at least four direct hits on the German U-boat in one of many encounters between Q-ships and submarines during a campaign now almost forgotten. Yet, during the Great War when the apparently unstoppable U-boats did their utmost to starve Britain into defeat, Q-ship officers and crews seemed, to an anxious population, like a reincarnation of the heroes who had fought off Spain’s Armada centuries before.

The Problem

I n 1913, Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, said he was “not convinced” that Germany’s fast-growing fleet of technically excellent submarines would be used against merchant ships and civilians. “I do not believe this would ever be done by a civilised power,” he said in response to a warning from his own staff. Churchill was wrong. Even as the carnage of the Western Front began, the U-boats were quietly slipping their moorings, intent on bringing the horror of war to Britain’s doorstep.

I n 1913, Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, said he was “not convinced” that Germany’s fast-growing fleet of technically excellent submarines would be used against merchant ships and civilians. “I do not believe this would ever be done by a civilised power,” he said in response to a warning from his own staff. Churchill was wrong. Even as the carnage of the Western Front began, the U-boats were quietly slipping their moorings, intent on bringing the horror of war to Britain’s doorstep.

By Christmas 1914, the Royal Navy had declared the North Sea a closed military area, stopping and seizing vessels carrying anything that could help Germany’s war effort. To the outrage of the Germans, that included food. As the blockade took hold, Admiral Hugo von Pohl, Chief of the Naval Staff, issued an order that was to change profoundly the waging of war at sea. From 18 February 1915, he declared, the waters around Britain and Ireland were to be treated as a war zone, and any vessel in this zone would be attacked without warning, regardless of nationality or flag.

The Solution

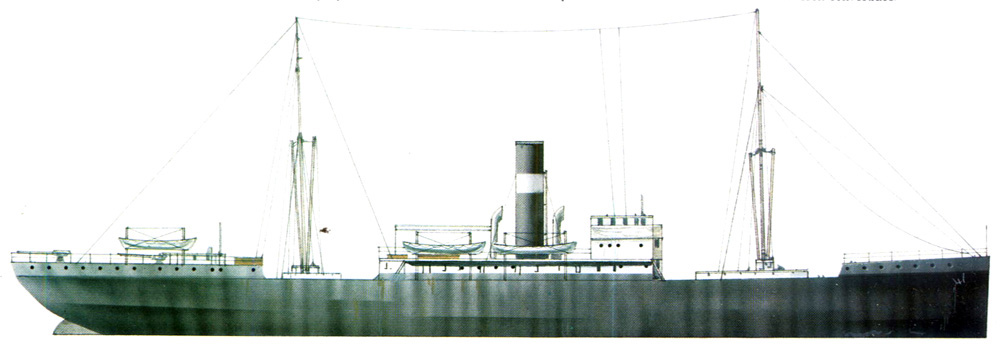

Winston Churchill was credited with the notion of pursuing U-boats with Mystery Ships, as they were first called. The war was only a few months old when he sent a telegram to Sir Hedworth Meux, Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth, asking him to send a disguised steamer to “trap” a submarine preying on shipping off Le Havre. There is no record of a Mystery Ship gaining success this early in the war, but the idea gained favour and the navy began assembling a small fleet of trawlers, coasters, tramp steamers, and sailing merchantmen.

The plan was for them to present an attractive target to a submarine and then, when the enemy was close enough to hit, drop the pretence and attack. For this to work, the disguise had to be perfect in every detail. Many U-boat crews included an ex-North Sea pilot or a man who had served aboard British merchant ships, and deceiving such experienced sailors would not be easy. Elaborate measures were taken. Guns were hidden behind the false sides of dummy cabins or bulwarks. Lifeboats were made to crack open like walnuts, revealing a ready loaded twelve-pounder. Even a hencoop could hide a Maxim gun. These disguised men o’ war were usually rather lowly ships, which would not have been expected to carry wireless; so aerial cable had to be concealed among other rigging, with wires painted to resemble manila rope. Later Q-ships were stuffed with timber to enable them to stay afloat and carry on fighting even after they were hit.

Officers and crew had to look the part too. Saluting was forbidden, and each man was given an allowance to buy civilian clothes of a type worn by merchant sailors. There was a little extra money for underwear, because crews on cargo ships usually dried their laundry around the deck, and a sharp-eyed U-boat commander would be certain to spot the distinctive Royal Navy issue flannel vests and drawers. Many Mystery Ships also had a “captain’s wife.” This was often some fresh-faced rating who dressed up in a wig and women’s clothes.

Tactics devised for the decoy vessels also demanded a high level of acting ability. The strategy was for a ship challenged or attacked by a submarine to appear as if it had been abandoned in a panic. Men would take to the boats and row for dear life. This “panic party,” as it was called, was crucial to convincing a U-boat commander the ship he was targeting had been left to her fate and was no threat, while her officers and gunlayers would be in their hiding places waiting to spring the trap. Panic party duty was no soft option. There was a real risk the men in the boat would be machine-gunned when the U-boat learned their true purpose. Even if the U-boat did not seek revenge, the job necessarily involved being in the crossfire.

Like actors, Mystery Ship men had to learn their lines. A blackboard was provided carrying details of the ship’s fictitious name, port of registry, and cargo details so they could convincingly answer questions posed by U-boat commanders, who usually demanded a merchant vessel’s papers before they sank her. Inevitably, perhaps, it was known as “the board of lies.”

Many in the Royal Navy, especially shellbacks who had served under Queen Victoria, thought the whole business was barmy. The little fleet of decoys was derided and dubbed “the Gilbert and Sullivan navy.” But the project had some powerful backers, including Churchill and Admiral David Beatty. And for the men who served aboard the disguised ships it was a deadly serious affair. All were volunteers. It was made clear they were expected deliberately to place themselves in harm’s way.

There were compensations for the unusual risks. A bonus in the form of hard lying money was paid, and there was prize money. The bounty for sinking an enemy submarine was £1000, divided into shares of £1 18s 1d, worth just under £100 today. An officer who played a significant role in an action might be awarded fifty shares.

Unlike men in the regular service—and soldiers at the front—there could be no surrender for the Q-ship crews. When the German Navy learned about the decoys it declared the men aboard them pirates who would be shot out of hand. The British soon discovered that on this point the Germans were—at least technically—right.

Deployment

In July 1915, Admiral Sir Stanley Colville, commanding Orkney and Shetland, sent the three hundred and seventy-ton collier Prince Charles to seek out submarines. Colville, like Beatty, was enthusiastic about the use of decoys. His considerable influence was later crucial in what became the Q-ship campaign.

Prince Charles was a rather shabby ship, built in 1905 to carry coal around the coast—a small but tasty morsel for a U-boat. On 20 July the collier spotted U 36 on the surface off North Rona Island in the Outer Hebrides. As Prince Charles drew near, the submarine fired a warning shot. The decoy vessel’s captain, Lieutenant William Mark-Wardlaw, ordered away the “panic party” and hid aboard with his gun crews. The U-boat closed in to sink the apparently abandoned collier. At six hundred yards, Mark-Wardlaw brought his concealed guns into action. Prince Charles was lightly armed, with a three-pounder and a six-pounder, but inflicted heavy damage. Out of control, the submarine presented its entire flank to Mark-Wardlaw, who steamed towards it at full speed. After another salvo from Prince Charles’s guns the submarine sank with more than half her crew. Fifteen, including her captain, were rescued.

HMS BaralongThe action electrified the navy’s high command. It came after two stunning successes where decoys were used in partnership with a submarine. In June, Taranaki and C 24 sank U 40 off Aberdeen. Then, four weeks later, Princess Louise and C 27 accounted for U 23 near Fair Isle. It seemed a weapon had been found at last to combat the U-boat threat. There was just one problem. Prince Charles had flown her red ensign throughout the engagement. This led the War Staff to make an inconvenient discovery: not one vessel in the Mystery Ship fleet had been commissioned as one of His Majesty’s ships of war. Under the terms of the Hague Convention, they were operating outside international law; so they were pirates indeed.

HMS BaralongThe action electrified the navy’s high command. It came after two stunning successes where decoys were used in partnership with a submarine. In June, Taranaki and C 24 sank U 40 off Aberdeen. Then, four weeks later, Princess Louise and C 27 accounted for U 23 near Fair Isle. It seemed a weapon had been found at last to combat the U-boat threat. There was just one problem. Prince Charles had flown her red ensign throughout the engagement. This led the War Staff to make an inconvenient discovery: not one vessel in the Mystery Ship fleet had been commissioned as one of His Majesty’s ships of war. Under the terms of the Hague Convention, they were operating outside international law; so they were pirates indeed.

This unfortunate oversight was hastily corrected, and the decoys were commissioned as tenders to naval vessels. At this time they were also given secret numbers, beginning with the letter ‘Q’—possibly because their main base was in Queenstown (now Cork), although the precise origin of the letter appears not to have been recorded.

Controversy

T he summer of 1915 saw numerous Q-ship successes. It was also a time of grave controversy. In August, a Q-ship was accused of a war crime, a charge that might well have been justified.

It happened the day a German U-boat sank the White Star passenger liner Arabic off the southwest coast of Ireland, killing forty-five civilians. The decoy ship Baralong, a small steamer flying the then-neutral Stars and Stripes, was in the area, and began scouring the sea for the submarine. Then Baralong’s wireless operator picked up an SOS message: a freighter, Nicosian, was being attacked just nine miles away.

Baralong was commanded by Lieutenant-Commander Godfrey Herbert, an experienced submariner who had volunteered for the Special Service. He immediately ordered full speed towards the Nicosian’s position. He and his officers and crew thought the freighter’s attacker had to be the U-boat that had (in their eyes) murdered the people aboard Arabic. This was to prove an important element in what happened next.

As Baralong came up with the stricken steamer, her people saw men in boats and a submarine, U 27, shelling the ship. Herbert quickly altered course to starboard, placing the Nicosian between him and the U-boat. He knew U 27 would appear from behind Nicosian’s bow ready to fire at him, so he posted Marines with rifles in Baralong’s bow. When the submarine cleared Nicosian the Marines were ready. “The Marines kept up an incessant rifle fire from the start and accounted for several of the gun’s crew before it was possible for them to retaliate,” Herbert noted in his report.

Then Baralong’s hidden twelve-pounders spoke. No fewer than thirty-four shells were fired, “mostly taking effect,” as Herbert laconically noted. The submarine sank in just over a minute, leaving her commander and a number of men in the water. These men swam to the pilot ladder dangling from the side of the abandoned Nicosian, clambered aboard and disappeared.

Herbert brought Baralong alongside and sent a party of Marines aboard Nicosian to find the Germans. In his report, Herbert said the Marines found six men who had been mortally wounded by lyddite shells. They were buried at once, he added.

Another version of events was soon to emerge. Witnesses, including one who claimed to have been aboard Baralong, said the Germans were shot dead in cold blood. One said the U-boat commander escaped the massacre by jumping into the sea, raising his hands in surrender. According to this account he was shot at least twice, in the mouth and neck.

Significantly, the official Royal Navy account did not exonerate Baralong. It concluded: “…the Germans were found in the engine room and the Marines, in hot blood, and believing they had to do with the men who had so wantonly sunk the Arabic in the morning, shot them all at sight.” Herbert went on to have a successful naval career and, in a later memoir, confirmed the truth of this account.

A Booby Prize

The Baralong affair did little to diminish the public’s admiration for the plucky little Q-ships and their crews of “live human bait,” as one senior officer put it. And in 1917, a few months after the slaughter of the Somme, the heroism of the decoys gave Britain a much-needed boost to morale.

On 30 April, Prize, a three-masted schooner of two hundred and twenty tons, was sailing slowly in a light breeze in the Western Approaches, the U-boat commanders’ favourite hunting ground. Prize was under the command of Lieutenant William “Willie” Sanders, a merchant officer from New Zealand who had volunteered for the Royal Navy soon after war broke out. On being promoted to lieutenant in February 1917, he was given command of Prize, a German trading vessel captured early in the war. When Sanders took her over she was Q 21, armed with three very well-hidden twelve-pounders.

As she ghosted along, the lookout sounded the alarm. A U-boat was in sight. It was U 93 commanded by Kapitänleutnant Adolf Edgar, Freiherr von Spiegel und Peckelsheim. Baron von Spiegel was having a successful patrol and had already dispatched twelve ships. His first inclination was to let Prize go, but his first officer changed his mind. The gunners aboard U 93 fired two warning shots and seven men aboard Prize hastily shoved off in the whaler, a perfect panic party. The U-boat then set about destroying the schooner, pouring round after round into her. As the shells crashed around them, Sanders, his officers and his gunlayers stuck at their posts, watching and waiting. Prize was sinking. Her mainmast had taken two direct hits; the living quarters and wireless room were on fire. Still Sanders waited. The U-boat closed to within one hundred yards for a last look at its victim.

Sanders had been watching the submarine through a spyhole, relaying its movements to his twelve-pounder crews as it approached. When he gave the order “Let go!” the gunlayers already had their sights accurately set. In their first salvo the forward gun on U 93 was annihilated. The submarine replied with a shot that hit Prize on the waterline, deflected upwards and crashed through the deck. Another round carried away part of the superstructure, badly wounding three men. But Prize managed to manoeuvre to bring her stern twelve-pounder into play. The submarine was taking a hammering. Von Spiegel joined his men at the guns. A shell from the schooner took off the head of a German gunner whose body smacked into von Spiegel, knocking him over the side. He saw U 93 “vanish into the depths of the ocean,” as he later recalled.

Von Spiegel and a handful of his crew were picked up by Prize, where men were stuffing mattresses and hammocks into the holes in her hull. Prize made it back to port, entertaining the German prisoners with cigarettes and cocoa. “After the war we can be friends,” von Spiegel told Sanders. “I am fighting for my country and you are fighting for yours. That is right and proper for both of us.”

Alas, it was not to be. On 13 August, Prize was back at sea in company with a submarine, D 6. Sanders and his men spotted a U-boat, U 48, and engaged her, scoring five direct hits at close range. The U-boat dived, listing heavily. The following day, Prize blew up with the loss of all hands. It was assumed her quarry had successfully escaped and returned to carry out a torpedo attack unseen. Nor had U 93 suffered the fate her captain feared. Her first officer managed to get her back to Germany. Still, Sanders was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Envoi

Fighting decoys are probably as old as sea war itself. They played a role in various campaigns against Barbary pirates and the captain of a privateer would have quickly found himself at home aboard a Q-ship. But the First World War marks the pinnacle of their achievement. More than two hundred were commissioned, sixty of them sailing vessels. Churchill wrote that they “afforded opportunity for some of the most brilliant and daring stratagems in the naval war.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.