Finest Hour 170

Books, Arts & Curiosities – The Men Who Went into the Cold

December 3, 2015

Finest Hour 170, Fall 2015

Page 40

Review by Alonzo Hamby

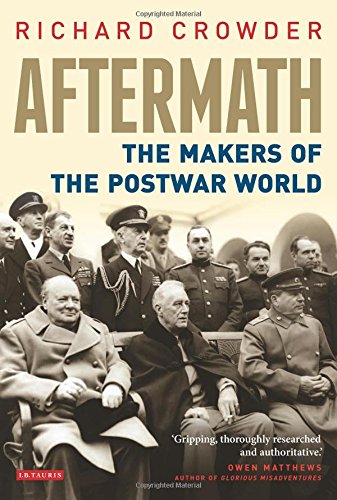

Richard Crowder, Aftermath: The Makers of the Postwar World, London and New York: I. B.Tarus, 2015, xii + 308 pages, $35. IBSN 978-1784531027

Most histories of the early Cold War, especially those written by Americans, give center stage to US statesmen, notably Harry Truman, Dean Acheson, and George Marshall. Richard Crowder, a youngish British diplomat educated at Oxford and Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, focuses his engagingly readable account on the other side of the Atlantic. His narrative provides equal time to such British figures as Clement Attlee, Ernest Bevin, and Duff Cooper. It also gives more attention to continental European leaders than they customarily receive.

Most histories of the early Cold War, especially those written by Americans, give center stage to US statesmen, notably Harry Truman, Dean Acheson, and George Marshall. Richard Crowder, a youngish British diplomat educated at Oxford and Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, focuses his engagingly readable account on the other side of the Atlantic. His narrative provides equal time to such British figures as Clement Attlee, Ernest Bevin, and Duff Cooper. It also gives more attention to continental European leaders than they customarily receive.

It is significant that a Labour government led Britain into the Cold War with remarkably little internal dissent. Bevin, a former trade union leader with a rudimentary formal education was at first glance an unlikely foreign secretary. He is perhaps too easily caricatured. The author quotes him as telling the eminent career diplomat Gladwyn Jebb, “Must be kinda queer for a chap like you to see a chap like me sitting in a chair like this….Ain’t never ’appened before in ’istory” (120). At times Bevin could be too rough and blunt for his own good— as when, in an incident Mr. Cooper passes over, he accused American leaders of supporting mass Jewish immigration to Palestine because “they did not want too many of them in New York” (quoted in Robert J. Donovan, Conflict and Crisis, 317).

His shortcomings, however, were more than offset by his conviction that Communists and their Soviet sponsors were enemies of freedom and hostile to the interests and values of the working class. Harry Truman never quite forgave the remark about Palestine, but nonetheless came to value Bevin as a trusted ally in the Cold War.

Winston Churchill plays a bit role in this book. Out of power and leading the Conservative opposition to Clement Attlee’s Labour government, he is largely treated as just another voice. Stressing the negative reaction of a few influentials such as Walter Lippmann to Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech at Fulton, Missouri, in 1946, the author understates its considerable impact in the United States. From time to time, moreover, Mr. Crowder stumbles with the trivia of American life and politics— Ferdinand Magellan, for example, was the name of the President’s private railway car, not the entire train—but such lapses are never serious.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Mr. Crowder rightly gives considerable attention to the establishment of the United Nations organization. He reminds us of the central role it was expected to play in world politics and shows us how it instead became a venue for great power rivalry. Eleanor Roosevelt, appointed by President Truman to the American delegation, serves as a case study of disappointed American hopefulness. Soviet ambassador to the UN Andrei Gromyko personifies his nation’s intransigent hostility.

We get a good sense of how the Cold War developed out of unnecessary Soviet excesses in what could have been simply an Eastern European sphere of influence. First came the American decision to support the Greek government against a Communist insurgency and to extend backing to a Turkish government that was under Soviet pressure. Mr. Crowder effectively demonstrates the way in which President Truman justified the policy by invoking liberal democratic principles, prefaced by the phrase “I believe.” This was quickly followed by a decision to frustrate a Communist drive for political power in Western Europe by an American program of massive relief and economic assistance, the Marshall Plan.

Especially critical in solidifying the emerging Cold War was the needless Communist coup in Czechoslovakia and the fatal defenestration of Jan Masaryk, a leader much esteemed in the United States. This event, deserving more attention than it gets, followed by the Berlin blockade, demonstrated that the wartime alliance was beyond repair. The logical conclusion to all this was the North Atlantic Treaty and establishment of NATO—a triumph of decisive, yet cautious, containment of Soviet ambitions and a logical conclusion to this fine narrative.

For reasons that are not apparent, however, the author ends his story with an account of the psychiatric breakdown and suicide of American Secretary of Defense James Forrestal. Whether he means simply to retell a dramatic story or to represent Forrestal’s tragedy as symbolic of a larger diplomatic failure is uncertain.

Alonzo Hamby is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History at Ohio University. His newest book is Man of Destiny: FDR and the Making of the American Century (Basic Books, 2015).

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.