Finest Hour 171

Books, Arts & Curiosities – His Courage Had Not Failed

March 20, 2016

Finest Hour 171, Winter 2016

Page 43

Review by Robert James

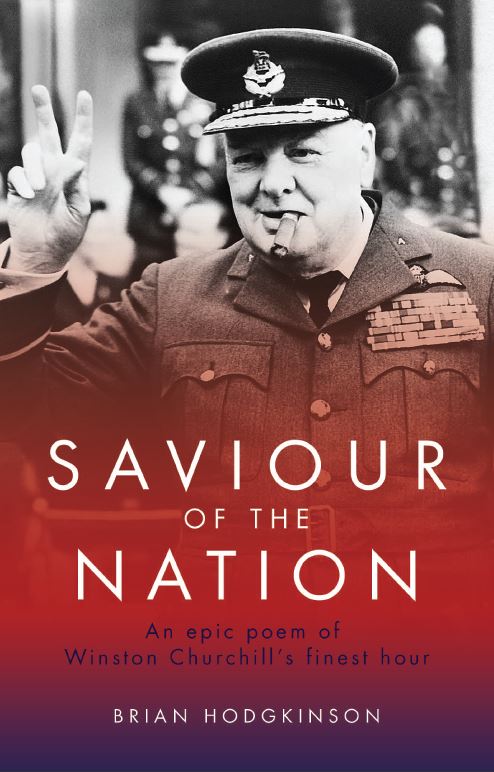

Brian Hodgkinson, Saviour of the Nation: An Epic Poem of Winston Churchill’s Finest Hour, Shepheard-Walwyn Publishers LTD, 2015, 186 pages, £10.00, US $15.95, CAN $18.95.

ISBN 978-0856835063

Ulysses. Aeneas. Dante. Satan. Winston Churchill. An epic poem focusing on Winston Churchill’s rise to power and defiance of Adolf Hitler attempts to join the ranks of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Virgil’s Aeneid, Dante’s Divine Comedy, and John Milton’s Paradise Lost. Well, why not? Churchill is an apt subject, after all, a historical figure of transcendent importance in twentieth-century history and the defeat of what many consider the most concentrated form of evil known to man. What better hero to choose for a modern epic poem?

Ulysses. Aeneas. Dante. Satan. Winston Churchill. An epic poem focusing on Winston Churchill’s rise to power and defiance of Adolf Hitler attempts to join the ranks of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Virgil’s Aeneid, Dante’s Divine Comedy, and John Milton’s Paradise Lost. Well, why not? Churchill is an apt subject, after all, a historical figure of transcendent importance in twentieth-century history and the defeat of what many consider the most concentrated form of evil known to man. What better hero to choose for a modern epic poem?

Reading Saviour of the Nation is a pleasant experience, providing a kind of History-Channel summary of Churchill’s opposition to Nazi Germany, beginning with a few scattered chapters touching on Hitler’s rise in 1932 and 1933, then rapidly moving to the heart of the tale, Churchill’s ascension to prime minister through to the Japanese attack on Pearl

2024 International Churchill Conference

Harbor (and the full commitment of the United States to war as Britain’s ally against Germany). The broad narrative scope touches upon all of the important moments in that solitary struggle, from the Battle of France and Dunkirk to the Battle of Britain to the Blitz to the invasion of Russia (with the other essential moments all carefully covered).

As history, however, one has to wonder precisely who Hodgkinson’s audience is intended to be. Neophytes would be better advised to take up a more approachable and informative text, like Ashley Jackson’s recent biography Churchill. Those of us in the know will find very few surprises at all in the text, which occasionally comes across like a very bright college student’s thesis paper, full of citations and odd little stories and quotes (which is entertaining, but few of these touches are likely to be unknown to those with a few books on the period under their belts).

This brings us to the question of Saviour of the Nation as a poem, of the artistic qualities Hodgkinson brings to the proceedings. As an epic poem, he has certainly chosen a fitting subject. Who better to match the wit and tongue of Odysseus, the drive of Aeneas to survive, the hope of Dante to retrieve something precious from the clutches of hell, and the pride of Satan fighting against all odds to remain defiant?

Hodgkinson certainly gets Churchill’s character correct. He has also centered on two themes for his epic: the memory of the wound of Gallipoli, which threatens repeatedly to undo all Churchill is fighting for, and even more potently, the ties Churchill has to the British people. Epic poems often focus on a failure as a spur to the narrative (Odysseus’s defiance of the Gods, his wounding of the cyclops Polyphemus), as well as the national character of the people who support the hero (the goatherd who recognizes Odysseus upon his return, and the elderly who are shamed by the actions of the suitors in Odysseus’ absence). Churchill’s connection to the common citizen is conveyed in thrilling terms quite often. The heart of the poem comes with one of Churchill’s morning-after visits during the Blitz:

He visited the stricken Londoners

When fires still raged, and ruined buildings stood

Like skeletons amidst the rubble heaps;

Where tiny paper flags—the Union Jack—

Waved bravely on some workers’ shattered homes.

…When Churchill came

Unsure of his reception, he was mobbed.

‘Good old Winnie,’ many of them cried.

‘We can take it! Give it to ‘em back!’

A woman shouted, ‘See he really cares.’

She’d seen that he could not restrain his tears.

I think Hodgkinson has his heart in the right place, but his poetic talents may not be up to the task. He does not seem interested in following all the traditional beats of the epic; there is no evocation of the muse, we do not begin in medias res, there is little sense of the divine. That I can accept, but what jars the ear is how little actual poetry there is in this poem. He has blank verse down pat, but so little of the poem is more than transcription of historical events. What irks is that Hodgkinson has a few moments in which he actually does rise to the kind of concentrated effect one hopes for from poetry, as in his description of the time when France had fallen and only Britain remained:

It was a moment outside passing time,

A place of stillness, like an ancient church

Whose years of prayer had sanctified the stone

And cleansed the air of every sound but one.

I wish Hodgkinson had reached for more of that level of expression, but he rarely does, which undercuts the value of Saviour of the Nation as a way to compress the experience of those times into passages one might remember fondly. For fans of Winston Churchill, I suspect Saviour of the Nation is worth reading, just as an oddity, a curio for the bookshelf. Hodgkinson is at work on a narrative poem on the entirety of World War II. One can only hope Saviour of the Nation is a clearing of the throat for a greater piece of poetry.

Robert James received his Ph.D. in English from UCLA in 1995. He is the author of the series Who Won?!? An Irreverent Look at the Oscars, available through Amazon.com.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.