Finest Hour 172

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – The Top Tories

June 12, 2016

Finest Hour 172, Spring 2016

Page 44

Review by David Hudson

Charles Clarke, Toby James, Tim Bale, and Patrick Diamond, editors, British Conservative Leaders, Biteback Publishing, 2015, 384 pages. ISBN 978-1849549219

This study of the leadership of the British Conservative Party illustrates what happens when political scientists are permitted to forage in pastures historians have long tended to consider their own preserve. The authors use several straightforward criteria to determine the relative effectiveness of leaders of the British Conservative Party from the time of Sir Robert Peel onwards. Charts, tables, and graphs lend a statistical verisimilitude to the overall conclusions and invite the reader to ponder whether there might not be a solid evidentiary basis both for and against commonly held judgments about political success and failure. Most of the Conservative party leaders under consideration became Prime Minister at least once, and in many (but not all) cases this study tends to confirm the generally held verdict as to whether a particular leader was a success or a failure in the position of party leader.

This study of the leadership of the British Conservative Party illustrates what happens when political scientists are permitted to forage in pastures historians have long tended to consider their own preserve. The authors use several straightforward criteria to determine the relative effectiveness of leaders of the British Conservative Party from the time of Sir Robert Peel onwards. Charts, tables, and graphs lend a statistical verisimilitude to the overall conclusions and invite the reader to ponder whether there might not be a solid evidentiary basis both for and against commonly held judgments about political success and failure. Most of the Conservative party leaders under consideration became Prime Minister at least once, and in many (but not all) cases this study tends to confirm the generally held verdict as to whether a particular leader was a success or a failure in the position of party leader.

The authors seek to assess the effectiveness of party leaders in terms of electoral success, at both national and constituency level, and attempt to link electoral success with the leader’s ability to craft an attractive and unifying message as Britain emerged into a new democratic age. The exigencies of mass politics and party unity may have left reduced scope for a certain kind of charismatic leadership, though leaders such as Robert Peel and Benjamin Disraeli were able to reconfigure the party message effectively for the masses who were Britain’s new masters by the end of the Victorian Age. Under their skilled leadership, a political philosophy emerged that was visceral, traditional, and at the same time forward-looking.

By contrast, leaders such as Arthur Balfour, Anthony Eden, Austen Chamberlain, and William Hague emerge as much less successful leaders both because they (for the most part) failed to win elections, and also because they failed to communicate effectively with either the party or the general public. In fact the hapless William Hague and his two successors in the Conservative leadership, Iain Duncan Smith and Michael Howard, were all unable to make headway against the savvy image makers of New Labour. The authors are willing to concede that “[A]ssessing political leaders is difficult,” and they acknowledge that “achieving these tasks is much easier for some than for others” (29).

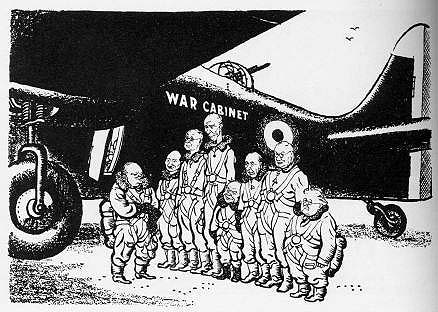

Surprisingly, Winston Churchill is found among the latter group, party leaders who performed statistically poorly in the study. John Charmley damns him with faint praise, assessing that he was “pretty much a failure” as party leader (238). In Churchill’s case, however, his stature as national leader between 1940 and 1945 enabled him to transcend party divisions. This fact, together with the massive leftward shift in European politics at the end of the Second World War, goes far to account for the Conservatives’ electoral catastrophe of July 1945. Charles Clarke concedes that when “only the results of 1950 and 1951 are considered, Churchill is the most successful twentieth-century Conservative leader in terms of seats gained, and the second most successful (after Baldwin) in terms of share of the vote increase. His case is perhaps the starkest example of the distinction between the national political leader (of a coalition), which Churchill patently was, and the leader of a political party, which, in a sense, Churchill did not become until after he had lost in 1945—if then” (52).

Surprisingly, Winston Churchill is found among the latter group, party leaders who performed statistically poorly in the study. John Charmley damns him with faint praise, assessing that he was “pretty much a failure” as party leader (238). In Churchill’s case, however, his stature as national leader between 1940 and 1945 enabled him to transcend party divisions. This fact, together with the massive leftward shift in European politics at the end of the Second World War, goes far to account for the Conservatives’ electoral catastrophe of July 1945. Charles Clarke concedes that when “only the results of 1950 and 1951 are considered, Churchill is the most successful twentieth-century Conservative leader in terms of seats gained, and the second most successful (after Baldwin) in terms of share of the vote increase. His case is perhaps the starkest example of the distinction between the national political leader (of a coalition), which Churchill patently was, and the leader of a political party, which, in a sense, Churchill did not become until after he had lost in 1945—if then” (52).

2024 International Churchill Conference

By contrast, Stanley Baldwin, who spent his later years as a member and subsequently the leader of a national coalition government, is (statistically at least) far the most successful of all Conservative leaders. Anne Perkins’ assessment is that “Baldwin made Conservatism not about politics, but anti-politics” and “shared understanding and sentiment…” (210). But the truth is rather more complex, and appeasement cast a long shadow. Baldwin did indeed have a knack for winning elections, but few would rate the 1930s as glory years for the Conservative Party. Such, alas, are the inherent limitations of this volume’s analytical models.

While this volume sheds some interesting light on the somewhat arcane business of leadership, it is hard to escape the conclusion that there is something mystical about those who are most successful at it. Still, this study does lay bare and map out as much of the anatomy of leadership in the modern Conservative Party as anyone could wish to know.

David Hudson teaches British history at Texas A&M University.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.