Finest Hour 172

“The Blood Test”: Churchill Writing on the Battle of the Somme

June 12, 2016

Finest Hour 172, Spring 2016

Page 32

By Robin Prior

The Battle of the Somme raged from 1 July to mid-November 1916. It was the largest battle the British Army has ever fought—or is ever likely to fight. When Winston Churchill came to write his history of the First World War (which he called The World Crisis) it was inevitable that he would pay considerable attention to this—particularly since he held very strong views about the manner in which it had been fought.

However, Churchill faced a particular difficulty in writing about the Somme. Earlier in the war, he had been First Lord of the Admiralty, during which time he had accumulated plentiful contemporary documents. These materials formed the basis of the first two volumes of The World Crisis, which covered the period from 1911 to 1915. Indeed, one-third of the material on this period consists of these papers and memoranda.

But the Dardanelles fiasco forced Churchill to resign. The period of the Somme saw him out of office and cut off from all official government communications. So when he came to write his narrative he lacked the foundation on which his earlier chapters had been based.

Finding the Sources

Nevertheless, Churchill was not without resources. He had been following the course of the Battle of the Somme closely, and in August, when the battle had been underway for a month, he sent the War Committee (the Cabinet Committee that oversaw the war) a memorandum which challenged the prevailing views of the conflict. He argued that the British army had made no substantial gains and suffered many more casualties than they had inflicted on the Germans. He backed up his claims with a highly detailed breakdown of casualty statistics, which had clearly been provided by sources inside the War Office or GHQ in France.1 The War Committee dismissed the paper without even giving it due discussion, preferring the statistics offered by General Robertson (Chief of the Imperial General Staff). He claimed, ludicrously, that the Germans had lost 300,000 men for every week of the battle—suggesting a total for the month exceeding one million men, a figure greater than the entire German army that was fighting at the Somme.2

2024 International Churchill Conference

So Churchill had two tasks in writing his chapter on the Somme: he had to find sufficient documentary evidence to meet his exacting historical standards, and he sought to vindicate his wartime position about respective British and German casualties.

To solve the first problem Churchill approached Sir James Edmonds, who had been appointed British Official Historian for a series of books about military operations on the Western Front.3 This was not an obvious move. Edmonds had served on the staff of the British Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig, during the war and, as official historian, was hardly likely to adopt an anti-Haig line. But that of course was clearly the line that Churchill would be taking with his well-known views on the battle and on the casualty statistics in particular.

Despite their different views, however, the partnership flourished. Edmonds supplied Churchill with accounts of the battle from the German side that he particularly wanted. These included the account of the German defence of the Schwaben Redoubt and the actions of the 27th German Infantry Division that Churchill used in The World Crisis.4

Moreover, Edmonds supplied his own account of some British actions as well. The material used by Churchill on the failure of the 8th Division against Ovillers on pages 1044–47 of the Somme chapter actually uses Edmonds’ words.5 There is a long account of the first hours of the battle from the British point of view on page 1044. The paragraph which starts “Very different were the fortunes of the British” down to “practically no damage to the German defences having been done in the long bombardment” was entirely written by Edmonds and incorporated into The World Crisis by Churchill without amendment.6 What is particularly interesting about this passage is that it does not reflect well on the British High Command.

The Right Tone

Despite the large amount of critical material he had himself contributed, however, Edmonds was not satisfied with the tone of the final product. When Churchill sent him the chapter for comment before publication, Edmonds was moved to reply: “in view of your high & esteemed position in the hearts of your countrymen I think you might cut out some of the sarcasm about the military leaders.”7

Churchill replied at length:

Of course the sarcasms and asperities can all be pruned out or softened. I often put things down for the purpose of seeing what they look like in print. Haig comes out all right in the end because of the advance in 1918. Without this the picture would be incomplete….But this Somme chapter certainly requires a strong addition showing the undoubtedly deep impression made upon the Germans by the wonderful tenacity of our attack. If you have anything that bears on this, perhaps you could bring it along with you.8

Edmonds did have some additional material. He provided Churchill with a quotation from Ludendorff’s memoirs to the effect that the German army was never the same after the Somme, and he drew Churchill’s attention to a passage from the history of the 27th German Division that highlighted the terror of holding the line against an intense British artillery bombardment. Both were incorporated in a new draft of the chapter by Churchill.

In the end, despite the “pruning and softening,” the chapter as a whole is a savage indictment of Haig and the High Command. Churchill is critical of where the battle was fought (against the most formidable defences on the Western Front), the lack of surprise, the vagueness as to the objectives, the insouciant response to the loss of 60,000 casualties on the first day, and, in the later stages of the battle, the premature disclosure of the tanks in mid-September.

Churchill was also the first to draw attention to the continuing high casualty rates in the middle stages of the battle, when the Somme degenerated into “bloody but local struggles of two or three divisions repeatedly renewed as fast as they were consumed, and consumed as fast as they were renewed.”9 He recognised that the casualties suffered by these divisions were as high (50%) as those suffered on the disastrous first day. The numbers might be smaller than for 1 July, but the attrition of the British army was continuing at the same rate.

Assessment

There is no consensus among historians about many of these matters, but the fact that so many were lost on the first day for such derisory gains stands as a condemnation of Haig’s plan and its ludicrous objective of sending a massed cavalry force through in the conditions then prevailing on the Western Front. Nor was Haig’s reaction to the first day (“varying results must be expected on a wide front of attack”) worthy of the sacrifice of his troops. Haig was not the “butcher” of legend, but in this regard his response fell well below the level of events. And as for the overall plan, Churchill was certainly more aware than Haig (and some historians since) that the days of cavalry charges were over and that the war had to be won by technological means. (As Minister of Munitions in the latter stages of the war, he was able to supply some of those means.)

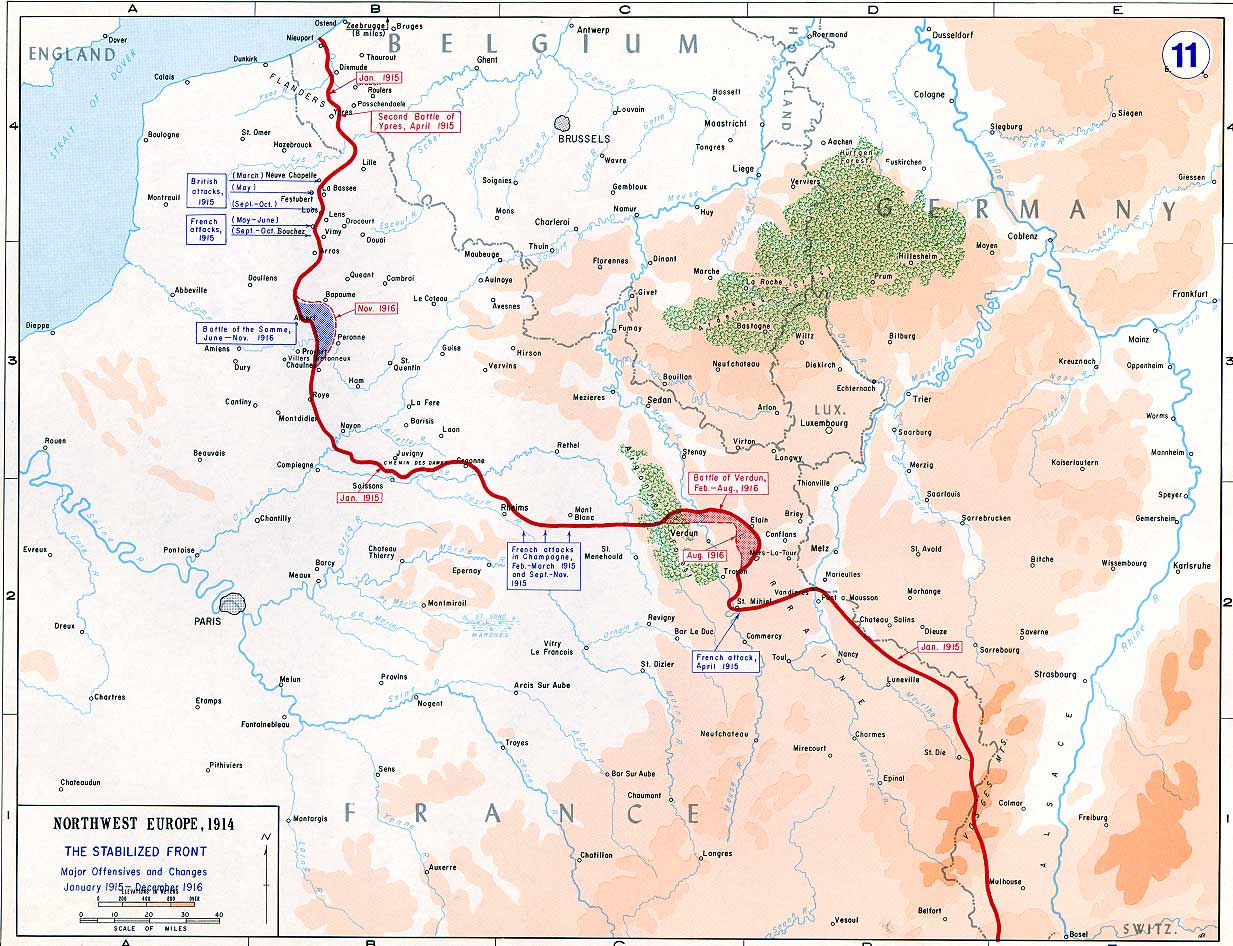

Other criticisms made by Churchill would not be accepted by most historians today. The British offensive was certainly directed against formidable defences, but it is not clear where else along the Western Front a campaign might have prospered. The French had launched unsuccessful battles in the Champagne and Artois in 1915; the British had fared no better at Aubers Ridge and Loos. The low-lying ground around the Ypres Salient in Belgium also had little to recommend it, as the campaign in 1917 was to demonstrate. There were no good options in 1916 and the area of the Somme was as good as any.

Nor should the lack of surprise be a matter for condemnation. Before the time when methods such as sound ranging had increased the accuracy of artillery fire, a long bombardment was required to neutralise enemy defences wherever the battle was fought. That this bombardment revealed the area of attack was unfortunate but also in 1916 unavoidable.

As for the tanks, Haig was undoubtedly correct in using them as soon as they became available. He wanted his army to obtain the best advantage from this surprise weapon, and he was rightly cautious in using small numbers in the first instance and making an offensive dependent absolutely on the performance of an untested weapon. As it was, 50% of the tanks broke down before they reached the start line. If this had happened in a large-scale battle, the result might well have been a fiasco.

Despite these strictures, Churchill’s final draft drew a positive response from Edmonds. He wrote: “I can find nothing against your general line of argument…the Somme chapter is a work of art, it takes up every important factor and shows extraordinary insight and is perfectly fair.”10

This was astonishing praise coming from an historian who would devote most of his life to the argument that the Somme was a British victory and was brilliantly planned. To which of these views Edmonds adhered remains a mystery.

Casualties

On one point Edmonds and Churchill would never agree, however: that of casualty statistics. Churchill had built his war-time indictment of the high command largely on the fact that the British suffered more casualties at the Somme than did the Germans. During 1923, when he was writing The World Crisis, he went to great lengths to investigate whether those earlier figures were correct. He requested detailed information from the British Embassy in Berlin about German casualties.11 The figures supported his wartime paper and he wrote in some excitement to Edmonds: “They [the figures] absolutely confirm the argument but with the most surprising features. I have in consequence recast the first three chapters with a new chapter full of graphics called ‘The Blood Test.’”12

Edmonds was not convinced. He warned Churchill that 30% should be added to all German casualty figures because they did not include the lightly wounded while the British figures did, and he supplied Churchill some statistics from the German VII Army Corps, which he claimed proved his point.13 Churchill did not accept this argument. He told Edmonds that if 30% were added to the German figures it would destroy the one soldier killed for every two wounded, which was deemed common for all three armies on the Western Front throughout the war. Nevertheless, Churchill was sufficiently worried by Edmonds’ argument to write again to the Berlin Embassy. He told them: “I am founding a considerable argument on these figures which in their present form bear out all I thought and wrote at the time in Official memoranda about what was taking place at the front. I am extremely anxious to be on the right side in all these calculations to make assurance doubly sure.”14 The Embassy replied a few days later enclosing a letter from the statistical experts at the German Reichsarchiv. In that letter they emphatically denied that the lightly wounded had been excluded from the figures. In response Churchill sent his figures to the Reichsarchiv for verification and they assured him that they were as accurate as any likely to be obtained.15 Hence Churchill’s conclusion in The World Crisis was that “in all the British Offensives the British casualties were never less than 3 to 2 and often nearly double the corresponding German losses.”16

These figures are still the subject of fierce debate today. They have been subjected to close scrutiny, however, by M. J. Williams in two seminal articles in the 1960s. I checked them again in my doctoral thesis in 1980, and in recent times an American historian and an economist have had a new look at them.17 The result is a complete vindication of Churchill’s stance. Attrition was at work at the Somme but it was working in favour of the Germans. Haig’s claim that he was wearing out the German army overlooked the point that he was wearing out his own army at a faster rate. Unless a completely new set of figures comes to light, we must conclude that Churchill’s wartime paper was substantially correct and it seems derelict of the War Committee that it dismissed it without investigation.

Well Worth Reading

All told then, Churchill’s chapter on the Battle of the Somme is, after more than ninety years, still well worth reading. In this and other chapters of The World Crisis he demonstrated that he could bring the assiduous research methods of the historian to events in which he had a personal stake. Many other politicians and generals in Britain joined in “the battle of the memoirs” in the 1920s and 1930s. Their efforts were invariably so partisan (Lloyd George’s memoirs are mainly memorable for his vituperative index) that they have not stood the test of time. The same can be said for some sections of The World Crisis, in particular the Gallipoli chapters, but even in these Churchill strived for some kind of balance. In the 1916–1918 volumes he was more successful. Here his breadth of mind and his determination to provide evidence for the points he made would make him a formidable historian. The chapter on the Battle of the Somme is one such example.

Robin Prior is the author of several works of military history, including Churchill’s World Crisis as History (1983). His most recent book, When Britain Saved the West: The Story of 1940, is reviewed on page 47.

Endnotes

1. This document is found in Winston S. Churchill, The World Crisis (London: Odhams, 1939), pp. 1054–59. There are many editions of The World Crisis available. The references used here can easily be located by looking for the chapter “The Battle of the Somme” in the particular editions.

2. See General Robertson’s paper for the War Committee dated 1 August 1916 in the Cabinet Papers, Cab 42/17/1, The National Archives, London.

3. The Churchill-Edmonds correspondence can be found at the Churchill Archive Centre, Cambridge in CHAR 8/203. The on-line version of that archive by Bloomsbury Press has been used here.

4. CHAR 8/203.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Edmonds to Churchill, 6 June 1926, CHAR 8/203.

8. Churchill to Edmonds, 7 June 1926, CHAR 8/203.

9. The World Crisis, p. 1050.

10. Edmonds to Churchill, 8 July 1926 and 6 August 1926, CHAR 8/203.

11. Lord D’Abernon (British Ambassador to Germany) to Lord Curzon (British Foreign Secretary whom Churchill used as a go-between), 26 July 1921, CHAR 8/188.

12. Churchill to Edmonds, 29 August 1923, CHAR 8/188.

13. Edmonds to Churchill, 14 October 1926, CHAR 8/188.

14. Churchill to Mr. Hume (British Embassy, Berlin), 12 January 1926, CHAR 8/204.

15. All this correspondence can be found in CHAR 8/204.

16. The World Crisis, p. 936.

17. See M. J. Williams, “Thirty Percent: A Study in Casualty Statistics,” RUSI Journal, February 1964, vol. 109, pp. 51–55, and “Treatment of German Losses on the Somme in the British Official History,” RUSI Journal, February 1966, vol. 111, p. 70. See also Robin Prior, Churchill’s World Crisis as History (London: Croom Helm, 1983), chapter 12, and James Mc Randle and James Quirk, “The Blood Test Revisited: A New Look at German Casualty Counts in World War 1,” Journal of Military History, July 2006, pp. 667–700.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.