Finest Hour 172

“Witty, Daring, and Direct”: Clementine Churchill and Eleanor Roosevelt

June 8, 2016

Finest Hour 172, Spring 2016

Page 10

By Sonia Purnell

Winston Churchill was, of course, half-American—an accident of birth that at times (notably during the Second World War) came in rather useful. The relationship with the United States of his Scottish-born wife Clementine was perhaps more complicated but at times also remarkably influential.

As a young woman, Clementine had harboured reservations about America. In the 1920s, she had been wary of the way it was displacing Britain as the world’s greatest superpower and was put out by President Coolidge’s refusal to forgive Britain’s debts from the Great War.

She had taken a detailed interest in politics and the international stage ever since her high society marriage of 1908. Since then her ever-increasing understanding of international affairs, close involvement in her husband’s career, and canny judgement of people had seen her become Churchill’s de facto chief adviser and strategist during the First World War. She continued to play a role demonstrably far greater than any other political wife in Britain for the rest of Winston’s career, but in the 1920s she was clearly no supporter of a great Anglo-American alliance.

Coming to America

It was only when she came to the United States in 1930—initially to convince her impetuous nineteen-year-old son Randolph that he was too young to marry a certain Kay Halle from Cleveland, Ohio— that she began to change her mind.

Once she had untangled Randolph from Kay, she decided she was having too good a time to rush back to Britain. She wanted a taste of American life, and to hear more about New World thinking. She attended speakeasies with her son, and rather more sedate luncheons with senators. She visited the White House—or rather gazed at it from the outside—and swam in the warm waters of the deep South. One of her favourite times was spent shopping in New York (soon referring to Fifth Ave just like a local), where she also indulged her passion for looking at art.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Soon she was reporting back to Winston that many Americans were actually “extremely nice,” and she was entranced at a newfangled idea of female “networking,” a term she had not come across before. It was clear that American women were more emancipated than their British cousins, and Clementine—who had been a suffragette supporter in her youth—came away smitten. Look at what women could do independently of their husbands!

Of course, when she returned to New York with Winston soon after, their visit was marred when he was knocked down by a taxi on Fifth Avenue. When news reached her of his injuries in her room at the Waldorf Astoria Towers, she was so upset she rushed off to the hospital forgetting to put on her shoes. She did not forget, however, the many kindnesses shown to her at that time and began to understand much better what made America and Americans tick.

That was just as well, for when Churchill became prime minister less than a decade later the British Commonwealth stood alone against the full might of Nazi Germany. France was falling, the Benelux countries had already gone, and now the forces of the Third Reich were preparing for an invasion of Britain, a country that had neither the money, the men, nor the armaments to defend itself for long. One minister of the time described Britain’s position in those dark times as one of unimaginable peril.

One morning in the summer of 1940, Churchill was shaving when Randolph entered his father’s bathroom in Downing Street to ask about Britain’s chances of survival. The elder Churchill said he had thought of the way through; that he had identified the only light that could shine the way. “I will,” he said as he swung round throwing his razor into the basin to dramatic effect, “drag America in.”1

From then on, this was the mission of both Churchills, acting, as they always did in a crisis, as a team. Together they entertained, persuaded, and ultimately almost bewitched a number of influential Americans who had President Roosevelt’s ear—Harry Hopkins, Averell Harriman, and Gil Winant were but three. The journalist Ed Murrow was another who came to believe fervently that Britain could be saved and was—equally importantly—worth saving. Sure, America did not enter the war as a combatant until Pearl Harbor some eighteen months later in December 1941, but it started supplying vital hardware and all sorts of other support in large part as a result of the Churchills’ combined force of personality.

The First Lady

Eleanor Roosevelt was another American visitor, who had to be charmed when she came to Britain in October 1942 to see for herself what war was like on the Home Front and to visit US troops. It was the first time the two women had met, and it was to have a significant impact on both of them—and the countries they served.

Clementine took the chance to observe her American counterpart carefully and learned much from how Eleanor received an ecstatic welcome everywhere she went. Eleanor could reach out in a way that politicians rarely managed; her informal but pragmatic style somehow oozed empathy; she took a concerned interest in everyone from all walks of life and the people, who were suffering greatly from the privations of war, were loving her dearly for it. Clementine was moved by her visitor’s success and inspired by how Eleanor used her own popularity to further the causes she believed in.

Ever eager to cement Anglo-American ties, Clementine wrote a gushing letter to FDR (whom she had not met at that point) about the vital effect Eleanor had had in boosting the morale of women and girls in particular. Certainly, part of her motive in writing was strategic, but the sentiments she expressed were genuine. “When she appears,” she wrote, the people’s faces “light up with gladness and welcome.” And on Eleanor’s handling of the press, Clementine added: “I was struck by the ease, the friendliness and dignity with which she talked with the reporters, and by the esteem and affection with which they evidently regard her.”2

A New Woman

From that point on, Clementine realised that she too could do more to help win the war by reinventing herself, by conquering her natural shyness and pushing herself forward.

The following year, 1943, she broke with all traditions and accompanied her husband to the Quebec conference with President Roosevelt. Eleanor was not there—FDR had sent her on a mission to visit US troops in the Pacific. In fact it would seem that the President was rather taken aback by the entirely novel idea of a leader’s wife attending one of these conferences—but Clementine was no ordinary wife. She did much to support and counsel her husband during the days and nights of meetings—as she so often did. Indeed, her influence behind the scenes was exceptional. But she also invoked Eleanor Roosevelt’s spirit in her absence with her first solo press conference.

Held after the end of the conference, in Washington, D.C., it was a triumph that helped install Clementine as a favourite with the American people. She was hailed by the US press for being a brilliant platform speaker, as well as being “witty, daring, and direct.” They had even—although she was by this point in her mid- fifties—decided that she was one of the prettiest of English women to be found, and in possession of engaging dimples.

She handled the journalists with aplomb, being by turns serious and humorous and doing much to boost the British cause. In fact, her press conference was almost certainly a deliberate ploy at bypassing an increasingly distant president to woo public opinion directly, a move essential at a time when British interests were clearly losing ground in the White House. And Clementine did just that. Indeed the Washington Times Herald was just one paper declaring the next day that Clementine was Churchill’s greatest asset.

And yet these admiring journalists knew only half of it. They certainly did not know how powerful she was behind the scenes, how she knew more about the conduct of the war than the British cabinet, or how she was in fact Churchill’s greatest influence, his closest adviser, spin doctor, vetter of his speeches, and in some ways even de facto deputy. She was also showing what a wonderful ambassador she was generally for her husband and her country.

Nor could the journalists present have guessed that the media maestro before them was deep down a naturally timid woman from an aristocratic but broken home, who was never quite sure who her father was and was haunted by fears of being penniless and homeless. She had learned to handle such a challenging public occasion with exquisite skill by scrutinising the methods and style of one Eleanor Roosevelt.

It was not all one way. There were many occasions during the war when the two women united to paper over the cracks in that vital Anglo-American alliance, and Eleanor became a great admirer of her British counterpart. Diplomacy then was so personal; the fate of the world relied heavily on the chemistry between two men, FDR and Churchill. And at times, they fell out; they had radically different outlooks, not least on empire and Soviet Russia. Clementine worked hard to paper over the cracks by strengthening her relationship with Eleanor whenever she could.

Differences

And yet until now the rapport between these two exceptional women has never been properly explored. They were married to the two men tasked with saving the free world from Hitler—but neither FDR nor Churchill thought much of the other’s wife. And neither did these very different women much like the other’s husband.

Eleanor was not Churchill’s type. He thought her an unappealing mix of opinion and disapproval who seemed to be frequently absent even at the height of war, was not bothered by dress or decor, and ran a White House notorious for unappetising food. Some have even said that Eleanor served such unappetising fare as a long drawn-out revenge for FDR’s affair with Lucy Mercer.

Churchill was particularly unimpressed that Eleanor’s cook Mrs. Nesbitt repeatedly served him creamy soup, even though he famously detested it. By contrast, Clementine kept files on the preferences of her guests and went to enormous lengths to serve them their favourite dishes, even in ration-struck Britain. Many a visitor was bowled over by what one called her “ambrosial” meals.

Eleanor meanwhile thought Churchill a drunken warmonger in danger of leading her husband astray and with offensive views on, among other subjects, women and the Spanish civil war.

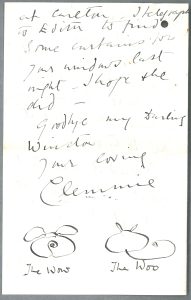

Clementine (who could be a little rigid at times) disliked how FDR presumed to call her Clemmie on their first meeting, a privilege normally earned by years of devoted friendship. She fretted that Churchill was too enamoured of the president and too emotionally transparent with a man who ultimately valued tactical advantage above any friendship. She knew FDR needed to be handled carefully and more than once intervened when she thought her husband in danger of alienating the American leader altogether. She knew how important US support was for Britain—and how such a precious asset could be thrown away by Winston’s romantic monarchist sympathies.

FDR—initially star-struck by Churchill—came to resent his legendary status, and he would eventually choose Stalin over Churchill when he thought it in America’s interests. He also thought Clementine difficult and resistant to his charms, when he much preferred unquestioning female adoration of the sort she was not prepared to give.

Similarities

The two women, however, grew to trust and admire each other more and more despite their contrast in style. They looked different—Clementine beautiful and immaculate; Eleanor a little plain and on occasion slightly windswept. But there was much they had in common.

They were of a similar age and aristocratic background. They shared a concern for the poor and a dislike of gambling and extravagance that led some to consider both of them to be crashing bores. Both had been schooled in England, and each had been taken in hand by an inspirational headmistress. They had each endured difficult and fearful childhoods and been considered plain when young. Both had lost an infant child and were married to egotistical men unwilling to impose discipline on their broods, at least some of whom were unhappy and sometimes unpleasant. Both felt inadequate as mothers but enjoyed being grandmothers; they both adored Christmas and excelled at planning for it. Both were prone to depression. The two brave and stoical women were also keepers of their husbands’ consciences.

Eleanor found Clementine just as fascinating. She thought her attractive, youthful and charming but initially constrained by her husband’s notion that women should remain in the background. She was consequently difficult to get to know. “She has had to assume a role because of being in public life,” Eleanor noted in her diary after their first meeting. “The role is now part of her but one wonders what she is like underneath.”3

Yet they relished each other’s company—who else could understand what it was like to be them? The bond between them grew even stronger after a poignant trip to Canterbury during Eleanor’s tour of Britain in October 1942, where as usual excited crowds of women and children surged forward to greet them. The next day the Germans bombed the city, and it was more than likely that some of those who had beamed at them so cheerily were among the casualties. Badly shaken, Eleanor wrote to FDR that the “spirit of the English people is something to bow down to.”4

Changing Behaviour

Clementine slowly lowered her guard. There were glimpses of what she perhaps really believed (most of which chimed with Eleanor’s views)—and even a certain female solidarity. At a small dinner party held in Downing Street in Eleanor’s honour, Churchill brought up the subject of the civil war in Spain. The American visitor annoyed her host by criticising the fact that more had not been done to help the republicans. Churchill was furious and rose from the table, but Clementine leaned across the table and said pointedly: “I think perhaps Mrs Roosevelt is right.” Astonished, Churchill signalled that dinner was over.5

Clementine may have welcomed Eleanor being willing to challenge her husband (few others did apart from her). Or maybe she foresaw trouble with the Americans if Eleanor left Britain angry with her hosts. In any case, it was evident that Clementine had her own mind and was not afraid to speak it—and this clearly impressed her guest. Perhaps Eleanor was more influential over Clementine, but it is also clear that during the war years at least Clementine was more powerful than she was. Clementine was immersed in every aspect of the war. Churchill took it for granted that she was his political as well as personal partner and once expressed surprise over drinks at the White House that FDR did not involve his wife more in government. “I tell Clemmie everything,” he told the president, who replied that he could not do the same with Eleanor because she might accidentally reveal vital information in her newspaper column if he did.6

Indeed, Eleanor had noticed how she had been sidelined since FDR had diverted his attention from welfare to weapons, writing sadly in one letter to her daughter that she thought it better to absent herself altogether from the White House so that what she called “important people” could take all the decisions.

Clementine’s importance merely grew and grew, however. After her D.C. press conference, she made more broadcasts on both sides of the Atlantic (some in tandem with Eleanor) and put more of herself into what she said. She lowered her reserve when meeting people on her tours of bomb sites or factories—becoming more chatty and informal. Her popularity began to soar, her mailbag bulged with letters, her personal power was becoming a force in its own right.

She exploited this new celebrity by raising the equivalent of $500 million—an astonishing sum from an effectively bankrupt country—for her Aid to Russia Fund to re-equip Russian hospitals damaged by the Nazi invasion. As one would for a Live Aid concert today, she recruited celebrities and sports stars to help her. Gradually she became the human face of Churchill’s government.

Previous critics became gushing fans of the new Mrs. Churchill. When her husband’s own popularity began to fall as the war ground on, hers only rose. American visitors found something familiar in her manner. “The dame is unbelievable,” noted the US Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau on a visit to Britain in 1944. “She is just like Mrs Roosevelt.”7

Delayed Recognition

After the war, of course, Eleanor was a widow and pursued her own highly successful career. Perhaps what she did at the United Nations on human rights was her life’s greatest work. In 1952 she was even touted as a possible presidential candidate.

Clementine meanwhile retreated into obscurity, and Churchill’s admittedly very large shadow, and is barely known today. Her role in helping Churchill during the war was so great, her involvement so vital, that it is bizarre and sad that her talents were not put to further use in aid of her country and the world as Eleanor’s were. I suspect Clementine may have felt a tinge of envy at Eleanor’s global success at a time when she found herself largely redundant. Churchill himself said that his life’s work would not have been possible without her.

The fact that Clementine did so much to help cement relations with Washington and its key figures was just one part, if a crucial one, of what she achieved. It is time that this is more widely understood.

Sonia Purnell is author of First Lady: The Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill, which is now available in paperback in the UK. It is published in the US as Clementine: The Life of Mrs. Winston Churchill.

Endnotes

1. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Volume VI, Finest Hour 1940–1941 (London: Heineman, 1983), p. 358.

2. Clementine Churchill to Franklin D Roosevelt, 1 November 1942, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, hereafter cited as FDR Library.

3. Eleanor Roosevelt’s diary, 20 October 1942, FDR Library.

4. Joseph Lash, Eleanor and Franklin (New York: Deutsch, 1977), p. 662.

5. Diary of Mrs. Roosevelt’s trip to London, Box 1364, FDR Library.

6. Jon Meacham, Franklin and Winston (New York: Random House, 2004), p. 21.

7. John Henry Blum, ed., The Morgenthau Diaries: Years of War 1941–1945 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1967), p. 336.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.