Finest Hour 174

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Master of the House

December 30, 2016

Finest Hour 174, Autumn 2016

Page 45

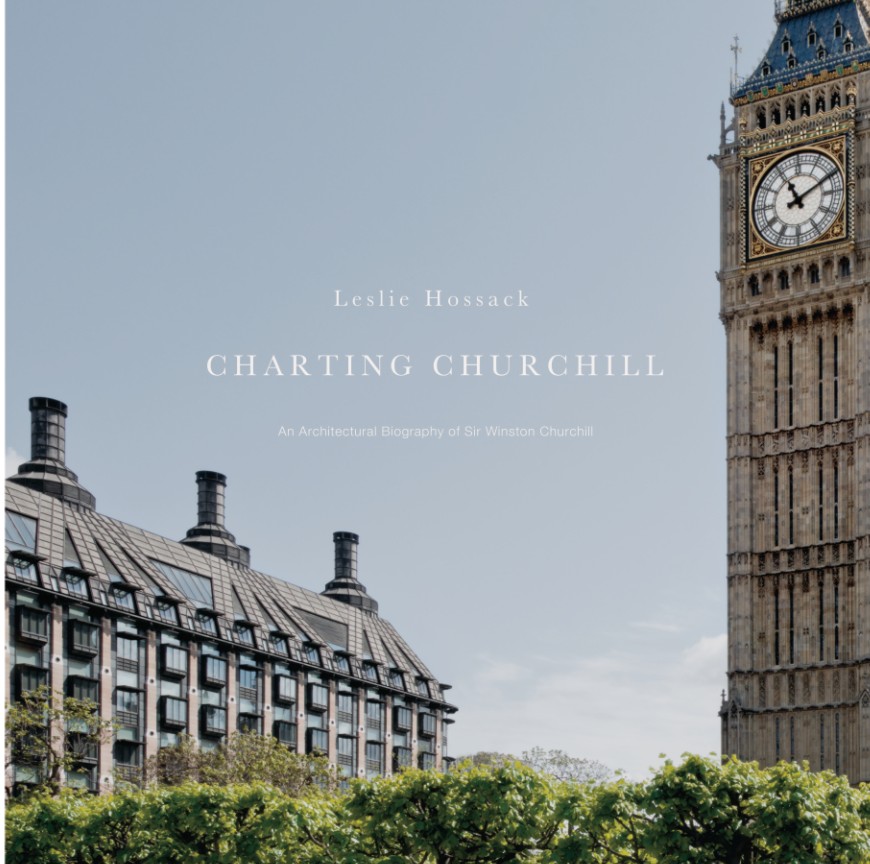

Leslie Hossack, Charting Churchill: An Architectural Biography of Sir Winston Churchill, 2016, CAD $196.49. Available exclusively online at www.chartingchurchill.com

Review by Stefan Buczacki

Professor Stefan Buczacki is the author of Churchill and Chartwell: The Untold Story of Churchill’s Houses and Gardens (2007). His latest book is My Darling Mr. Asquith: The Extraordinary Life and times of Venetia Stanley.

There is a late nineteenth-century volume in my library in which the author begins his introduction thus: “There are already so many books in the world that it is incumbent upon anyone writing another to justify its existence.” It is a maxim I have used many times, but when Leslie Hossack’s book arrived on my desk, my first impression was that this glorious and sumptuous work surely had no need to defend itself. It is without doubt the most beautiful book ever published about Churchill’s life; it has the finest photographs, and it ventures down some seldom explored by-ways. And it is innovative in offering us such unexpected images as those of his tailor’s premises and his London wine merchants, as well as of more familiar and expected places: the Houses of Parliament, Chartwell, and Blenheim Palace.

There is a late nineteenth-century volume in my library in which the author begins his introduction thus: “There are already so many books in the world that it is incumbent upon anyone writing another to justify its existence.” It is a maxim I have used many times, but when Leslie Hossack’s book arrived on my desk, my first impression was that this glorious and sumptuous work surely had no need to defend itself. It is without doubt the most beautiful book ever published about Churchill’s life; it has the finest photographs, and it ventures down some seldom explored by-ways. And it is innovative in offering us such unexpected images as those of his tailor’s premises and his London wine merchants, as well as of more familiar and expected places: the Houses of Parliament, Chartwell, and Blenheim Palace.

2024 International Churchill Conference

So much for this large, splendid, if costly volume and what it is; but now for what it is not. It is certainly not, as Ronald Cohen in his foreword suggests, the first to tell the Churchill story “via the buildings…which were part of his life.” Nor does the book even cover all his residences, because there are several inexplicable exclusions. For instance, his first, albeit brief, childhood home at 48 Charles Street in Mayfair was arguably the most attractive of all the town

houses in which he lived and is ignored for no obvious reason. That may be thought a minor matter, as is the absence of the Churchill retreats like Hoe Farm. But there are two much more important and quite astonishing omissions. First, where is Chequers, the Prime Minister’s official country residence, which meant so much to Churchill and where he spent a considerable and hugely important amount of time? And second, where is Lullenden? This ancient house on the borders of Sussex, Surrey, and Kent was Churchill’s first country home, bought during the First World War and which he and Clementine owned from 1916 until late 1919. Lullenden was pivotal in Churchill’s life and was where he first acquired his taste for land ownership. Without Lullenden there would have been no Chartwell; and it is a visually arresting house too, so the book is much the poorer without it.

Given the cost of the book, it is reasonable to quibble over some of the images, photographically good as they may be. The printing has sometimes let the author down, and some plates are not so crisp as one feels entitled to expect. Moreover some shots are just odd: for instance why show the rear of Lord Randolph’s house at 2 Connaught Place and not its more attractive front, albeit the scope for a good camera angle there is more limited? The image purporting to show 11 Downing Street, Churchill’s home when he was Chancellor of the Exchequer, is in fact a view of the entrance to Downing Street, with No. 11 barely discernible in the distance. And the image captioned “10 Downing Street” is even worse, it merely shows the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Cabinet Office, with the Prime Minister’s residence completely invisible.

And then there is the absence of any traffic in the photographs. In her introduction, Hossack states: “During my post-production process, these images are carefully crafted to look the way I feel the buildings might have appeared decades ago. Is this documentary photography or fine art photography? For me, it is simply my art.” I have no real argument with this if it helps a house to be seen more clearly. I do think, however, it is misleading to alter the appearance of the property itself, as seems to have been done with 28 Hyde Park Gate, where the blue plaque of today is missing. If the intention was to try and turn the clock back and show the buildings as Churchill saw them, it should be pointed out that all have changed, some practically beyond recognition.

If you are seeking a definitive illustrated account of all the residences Churchill occupied, this is not it, and the text does not reveal anything of which an average Churchill student would be unaware. There are also some elementary errors: for instance, legally Chartwell is not and never was Chartwell Manor. Leslie Hossack, nevertheless, is clearly a photographer of great merit, and if you want a truly glorious and sumptuous evocation of Churchill’s life, her book is unlikely ever to be bettered.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.