Bulletin #113 - Nov 2017

Darkest Before the Dawn

November 11, 2017

Review by Michael F. Bishop

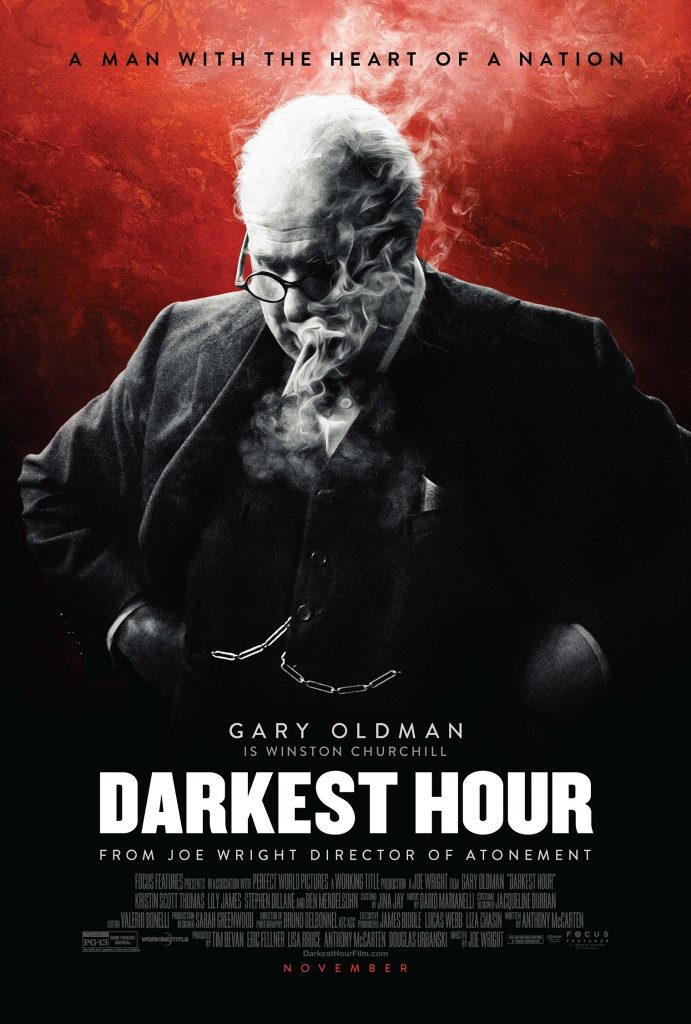

Darkest Hour released by Focus Features, directed by Joe Wright and starring Gary Oldman and Kristin Scott Thomas. Written by Anthony McCarten.

There is a lazy journalistic trope that suggests that films about Winston Churchill are a common occurrence, but Darkest Hour, directed by Joe Wright and starring Gary Oldman as Churchill, is the first major cinematic release about the great man since 1972’s Young Winston (with the regrettable exception of the dreadful Churchill, which defaced a tiny number of screens earlier this year before disappearing without a trace).

Most portrayals of Churchill have been in television dramas, and oddly, most of those have avoided the most dramatic chapter of his remarkable life: his earliest days as prime minister. They have instead depicted him in the political wilderness (Richard Burton, Robert Hardy, Albert Finney), in old age (John Lithgow), or in infirmity (Michael Gambon). Recently, only Brendan Gleeson has portrayed Churchill the warlord—but in a rushed storyline that condensed long years of war into less than two hours.

Darkest Hour devotes two full hours just to Churchill’s first month as prime minister, a wise dramatic choice that heightens the excitement of the film. It opens with the fall of Neville Chamberlain (Ronald Pickup) and accurately depicts the resistance on the part of many Tories to the elevation of Churchill. The coincidental and fateful invasion of Western Europe by Hitler’s forces on the very day of Churchill’s appointment sets up the dilemma that dominates the rest of the film—whether to resist the Nazi tide or to negotiate with “that man.”

2024 International Churchill Conference

Churchill’s chief rival for the premiership, and the preferred candidate of most, was the Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax (Stephen Dillane), who forcefully advocates negotiation with Hitler through Italian intermediaries. With the intermittent support of Chamberlain, Halifax harries Churchill in Cabinet and rejects the new prime minister’s policy of defiance. These bitter debates are interspersed among powerful depictions of Churchill’s three great speeches of that time: his first address to Parliament as prime minister on 13 May, his first radio address as prime minister on 19 May, and his mighty “We shall fight them on the beaches” speech of 4 June (in the film the latter speech appears to be delivered on 28 May, a vexing but forgivable act of dramatic compression).

Gary Oldman inhabits the role of Churchill, capturing his wit, grit, and determination, and even his impish smile. Wreathed in cigar smoke, with a voice that ranges from a slurred mumble to a stentorian roar, Oldman looks and sounds the part (kudos to makeup wizard Kazuhiro Tjuri, who encases the slender Oldman in the skin of Winston Churchill—even in the brightest light, the effect is flawless). But the real genius of the performance is in the energy that Oldman brings to the role. Churchill is accurately depicted as the “human dynamo” his contemporaries thought him to be. It is by far the greatest portrayal of Churchill ever captured on film.

Oldman naturally dominates every scene, but the performances are uniformly strong. Of particular note are the ethereal Kristin Scott Thomas, who beautifully captures the strength, elegance, and grace of Clementine Churchill, and Ben Mendelsohn, who perfectly conveys the awkward dignity of King George VI. The relationships of these two figures to Churchill are sensitively captured as well, from the profound affection (and occasional exasperation) that Clementine felt for her husband, to the growing respect that the King felt for Churchill after his initial dislike and distrust.

The superb script by Anthony McCarten and the deft touch of Joe Wright have conjured a thriller out of events that, while earthshaking in importance, are not inherently cinematic. It is no easy thing to make the arguments of men in conference rooms exciting, but in this as in much else, Darkest Hour succeeds brilliantly.

By Hollywood standards, the film demonstrates a remarkable fidelity to the historical record; the liberties taken are for the most part minor. Much of the action is set in the Cabinet War Rooms, which in reality were not yet in use. Churchill is depicted as moving immediately into 10 Downing Street upon his elevation, when in fact he remained in Admiralty House for a time.

More far-fetched is a wholly invented scene late in the film when Churchill improbably descends into the Underground and asks the working-class people around him whether they think England should keep fighting on. This sentimental diversion has its amusing moments, but the film would have been even better without it. What can be said in its defense is that it foreshadows Churchill’s real-life interactions with the working classes later in the war, as he visited their bombed neighborhoods and wept at their courage in the face of misfortune. And it is the case that many working class people were stauncher in their resistance to Hitler than some of their supposed social betters.

Darkest Hour is a triumph; an entertaining and substantive film that celebrates human greatness and glories in the power of the English language. Its popular and critical success, for which Churchillians should devoutly wish, would encourage legions of new admirers to learn more about the man who A. J. P. Taylor called “the saviour of his country.”

Watch the film’s official trailer here.

Michael F. Bishop is the Executive Director of the International Churchill Society.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.