Finest Hour 169

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – A Spoiled Peace

November 10, 2015

Finest Hour 169, Summer 2015

Page 42

Review by Erica L. Chenoweth

Isaiah Friedman, British Miscalculations: The Rise of Muslim Nationalism, 1918–1925.

Transaction Publishers, 2012, 394 pages, $59.95.

ISBN 978-1412847490

With the centenary of the First World War and continued tumult in the Middle East, Isaiah Friedman’s British Miscalculations: The Rise of Muslim Nationalism, 1918–1925, is a timely read. Friedman, a professor emeritus at Israel’s Ben-Gurion University and author of two other books on the region, briskly but thoroughly covers these fateful years.

With the centenary of the First World War and continued tumult in the Middle East, Isaiah Friedman’s British Miscalculations: The Rise of Muslim Nationalism, 1918–1925, is a timely read. Friedman, a professor emeritus at Israel’s Ben-Gurion University and author of two other books on the region, briskly but thoroughly covers these fateful years.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Friedman’s scholarship sharpens our picture of the dark, complex, and exciting times after the Great War. In his own account of these events, The Aftermath, Churchill wrote that “statesmen in crisis…have often to take fateful decisions without knowing a very large proportion of the essential facts.” With a cascade of memoranda, telegrams, letters, speeches, and other primary sources, Friedman shows how much was missing in the muddled handling of freshly-occupied regions by uncomprehending actors, both generals and statesmen.

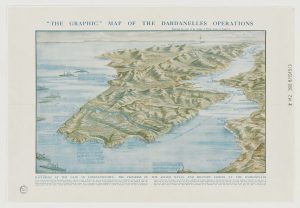

Friedman focuses on Britain’s relations with the Ottoman Empire during and after the First World War, especially the new state of Turkey, but also touches on other predominantly Islamic regions, including Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, Palestine, and Afghanistan. He argues that Britain and the Allies might have crafted a more friendly peace between themselves and the Middle East but for opportunities missed or mishandled.

The last chapter, a bit frazzled in presentation, suggests that peace between Jews and Arabs in Palestine was also possible for a time but bungled by the British. Instead, a “basic misconception of Arab sensibilities sparked a flame of religious / nationalist feeling that finally drove the European powers out of the Middle East” (17). When time was ripe for peaceful discussions between leaders of the region—when Churchill recognized that “every day’s delay in these loosely knit but inflammable communities was loaded with danger”—the Allies buried their heads in the soon-to-be-stillborn Treaty of Sèvres, while “unfriendly elements loaded their rifles and made plans.” Britain failed to anticipate the shock to Muslims from dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire and how quickly they would come to favor nationalist movements over administration by “infidel” Allied powers.

Friedman presents the facts with the blinding clarity of hindsight: his fourteen chapters recount misstep after misstep. Leaders of the Middle East, rebuffed or ignored in their attempts at renewed relations with Britain and the Allies, made secret deals and pacts with each other and with the Soviets, who eagerly insinuated themselves into the unstable region. The British government supported men unfit for senior positions, misunderstood the aims of Arab leaders, and ignored the best-informed and most insightful Britons, such as Churchill and “men on the spot” like Colonel Richard Henry Meinertzhagen.

Despite the diplomatic skill of Arab leaders, the British government fell into a grievous error: the “loosing of the Greek army into Asia Minor,” in Churchill’s words, which allowed “all the half raked-out fires of Pan-Turkism…to glow again.” Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Foreign Secretary George Curzon wanted to maintain a Greek foothold in Asia Minor. Friedman portrays them both as anti-Turkish backers of a new Hellenic empire, which they hoped would become a friendly, formidable power in the eastern Mediterranean. But the portraits of these men are incomplete; Churchill observed in Great Contemporaries, “you could hardly imagine two men so diverse as Curzon and Lloyd George.”

Friedman gives a more complete picture of Mustapha Kemal, the founder of modern Turkey, and the Emir Feisal, who was placed on the throne in Iraq. He casts Churchill as hero twice: as one of the few Cabinet members who gave thoughtful, though unheeded, advice on the region; and as the savior of British military forces in a chapter describing the tragic Mesopotamian campaign—which began in 1916, two years before the range of dates in the book’s subtitle. Friedman acknowledges Churchill’s position as War Minister starting in 1919 but fails to mention his move to the Colonial Office in 1921.

This book is suitable for a specialist or a diligent student. David Fromkin’s A Peace to End All Peace and Churchill’s own account provide needed ballast for the general reader. Each chapter of Friedman’s book has its own bibliography, but missing or weak transitions between chapters make them seem like separate articles instead of a book. Important characters and groups receive no introduction or are introduced two hundred pages after their first mention. Editorial irritants abound: erroneous words; erratic punctuation; missing spaces, words, and letters; and repetitious passages. More serious errors, such as confusing the date of Curzon’s resignation from the Foreign Office in January 1924 with that of his death in March 1925, are harder to forgive but less frequent. Despite these imperfections, the book is a formidable work of scholarship and would be even more worth reading if corrected and improved for a second edition.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.