Finest Hour 169

The Dardanelles: An Australian Perspective

November 10, 2015

Finest Hour 169, Summer 2015

Page 10

By Harry Atkinson

Harry Atkinson serves in the Royal Australian Navy.

“The British Empire itself seemed knit together by ties which none but its citizens could understand. What combination of events could ever bring back again to France and Flanders the formidable Canadians of the Vimy Ridge; the glorious Australians of Villers-Brettonneux; the dauntless New Zealanders of the crater-fields of Passchendaele; the steadfast Indian Corps which in the cruel winter of 1914 had held the line by Armentieres?”

—Winston S. Churchill, 1948

2024 International Churchill Conference

Australians, with a sense of humility, reverence, and overwhelming pride, pause each year to remember the Dardanelles campaign. It is now 100 years since the campaign began and Gallipoli became a part of Australian folklore. Many raise the question, why Gallipoli? Why did a campaign that was such a major failure, tragedy, and mistake become such a poignant symbol for Australia and Australians?

On 25 April 1915, Australia as a self-governing nation was only fourteen years, four months, and twenty-four days old. The country was still going through puberty, its people still learning what it meant to be Australian and what mark they could make on the world. Instead of having time to discover these things in peace, the young nation found itself quickly through war. The Dardanelles, specifically Gallipoli, was the premature turning point. Britain, the doting old mother, turned to the scruffy young boy and said, “stand up, you are a man now.”

Gallipoli will always be regarded as the event in which Australia was forged as a nation, forged in a war that many, especially today, believe should not have involved their country at all. Unlike today, however, Australians in 1915 did not consider themselves more Australian than British. Australians were patriotic members of the British Empire. The majority of people were either first or second generation Australian, and their connections with the mother country remained strong. The servicemen who signed up for the war did not join to fight for Australia. They joined to fight for the British Empire.

Australian and New Zealand soldiers landing at ANZAC Cove in April 1915 as depicted by Charles Edward DixonThe enthusiastic young men and women who clambered onto the steamers, heading northwards, were excited. This trip was an adventure. They had grown up listening to stories told by their parents and grandparents about Britain and Europe. Many believed that they would not be gone for long and that they would be giving “‘Jerry’ a good hidin’!”

Australian and New Zealand soldiers landing at ANZAC Cove in April 1915 as depicted by Charles Edward DixonThe enthusiastic young men and women who clambered onto the steamers, heading northwards, were excited. This trip was an adventure. They had grown up listening to stories told by their parents and grandparents about Britain and Europe. Many believed that they would not be gone for long and that they would be giving “‘Jerry’ a good hidin’!”

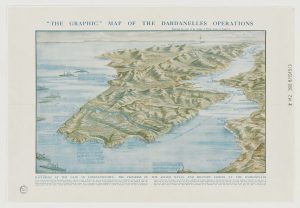

Australian soldiers first went ashore in Egypt, where they started to train around Cairo. At first the British did not know what to do with the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). Left in limbo for quite some time, the young soldiers grew restless, and incidents followed. Then, as battle raged on the Western Front, Winston Churchill and others searched for ways to break the deadlock. The Dardanelles plan was brought forward, and the naval battle began.

Into Battle

T he naval battle, like the entire subsequent campaign, was a complete disaster. Many British, French, and Commonwealth warships were sunk in the process. However, one Allied vessel was able to duck and weave through the Turkish defences within the passage: an Australian submarine called AE2. The boat sank a Turkish destroyer and was able to reach the sea of Marmora. AE2 remained in the fight for five more days before she took irreparable damage. The captain, Lieutenant Commander Stoker RAN, was forced to scuttle the boat and surrender.

To support the naval forces, the overlords decided a land invasion of the Gallipoli peninsula was vital. The AIF was the first on shore, landing at a place now known as ANZAC Cove. This beach, however, with its razor-sharp cliff tops and jagged rocks, was not the area where the Australian soldiers were meant to land. The rowing boats they were given drifted, and they found themselves in a dangerous and difficult situation. Quickly they started to take casualties, and this is where the Australian story truly begins. In the battle, Australian soldiers began to show uniquely Australian traits. They had a certain way of going about their business. In place of the British stiff upper lip, Australians exhibited what is called larrikinism, an Australian word for acting with apparent disregard for social or political conventions. Loyalty to one’s mates solidified into what it meant to be an Australian.

The Home Front

A s the boys fought tooth and nail for every inch of land on Gallipoli, life in Australia at first carried on much as normal, though news of what was happening with the AIF was on everybody’s mind. Then, the first telegrams with casualty lists began to come through. As the list of those killed in action began to grow, it became clear that entire communities had been destroyed. Brothers, husbands, sons, and lovers were all gone, and they all had one thing in common, Gallipoli.

Australians on the Home Front also came together through hardship. Communities kept busy creating care parcels for the AIF. In their letters home, the men at Gallipoli complained of the constant meal of dried biscuits and bully beef. Since Australia was so far away, a food had to be designed that would last the long journey to Gallipoli. Soon care packages began to contain a new type of biscuit. From rolled oats, flour, desiccated coconut, sugar, butter, golden syrup, baking soda, and boiled water came the famed ANZAC biscuit.

To this day ANZAC biscuits are a staple in every Australian kitchen, as Australian as custard creams are English. While they may no longer be savoured in a trench with Turkish bullets whirling overhead, ANZAC biscuits are an everlasting memory of Australia’s involvement at Gallipoli.

The loss of life was truly incomprehensible for Australians. More British and French may have died at Gallipoli, but relative to its population Australia’s losses were immense. As returning troop ships entered the port of Fremantle on the West Australian coast, the true scope of the horror began to be seen. Young men who had left filled with excitement and energy came home broken mentally and physically. Bitterness and anger swept over the Australian people. Emotional attachment to Britain and the Empire started to diminish, although ties remained firm until the Second World War.

Australians continued to fight in the First World War until the end. They fought in the deserts of the Ottoman Empire and in soggy trenches on the Western Front. The Royal Australian Navy patrolled the oceans from the Far East to the Mediterranean in search of German adversaries, and pilots in the Flying Corps supported their British counterparts in skirmishes over the Middle East and Europe.

But the men who came back from Gallipoli were truly scarred. The few who managed to survive the campaign unscathed were tested again elsewhere and considered the lucky ones to have been the wounded who were returned home to Australia.

Churchill’s Reputation

I n Australia, Churchill is blamed for many of the mistakes that transpired during the dreadful months the AIF struggled at Gallipoli. As an Australian myself, however, I regard this as an uninformed view. There were many reasons why the Dardanelles campaign failed. First among these was the inadequate command and control structure that existed within the British government and its military. The Prime Minister, Asquith, did not create a suitably coordinated framework for directing the war. Churchill did not make the same mistake in 1940.

Winston Churchill for me will always be an inspiring character, a man who defended the Western world from tyranny and all his life showed great courage. He may not have been perfect, and he did make mistakes, but he fought for what he believed and always tried to do right.

Under any circumstances, the Dardanelles campaign was a risk but one that might have shortened the war. The failure of the effort led to a dark time in Churchill’s life when he was forced out of the Admiralty. Not many Australians know that Churchill then secured a commission as a lieutenant colonel in the British Army and fought in the trenches as a Battalion Commander with the Royal Scots Fusiliers. Tinted photograph of ANZAC Cove

Tinted photograph of ANZAC Cove

Australia Today

As Australians look back on the events of 100 years ago, they should reflect on how far their nation has come. Today Australia is clearly a country that stands on its own and is no longer a boy holding his mother’s hand.

For most of the past century Australia has commemorated 25 April 1915. On ANZAC Day veterans and current members of the military don uniforms and medals to march through cities and towns all over the country. During the sombre parade, Australians clap and cheer as the servicemen pass. Afterwards takes place a truly Australian experience, as everyone raises a glass and remembers the men who fell in times of conflict. Remarkably, a battle that took place 100 years ago, and which no longer has any living survivors, still takes centre stage on ANZAC Day.

In the past few years there have been legitimate efforts to introduce new elements to ANZAC Day. Veterans of more recent conflicts have pushed for more support in the struggles that they will continue to have because of their service. Naturally, as a serviceman I hope that the government will dedicate sufficient funds to these needs.

Gallipoli can be a politically sensitive subject. The men and women of 1915 are suitably honoured for the losses they suffered. We should remember this as we go forward and honour all soldiers, sailors, and airmen who have worked to defend Australia over the past 100 years.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.