Finest Hour 174

Winston Churchill and the 1951 Festival of Britain

May 12, 2017

Finest Hour 174, Autumn 2016

Page 22

By Iain Wilton

Iain Wilton recently completed his Ph.D. at Queen Mary, University of London. He has also written a major biography of the English sportsman, writer and politician C. B. Fry; among much else, it covers each of Fry’s key encounters with Churchill.

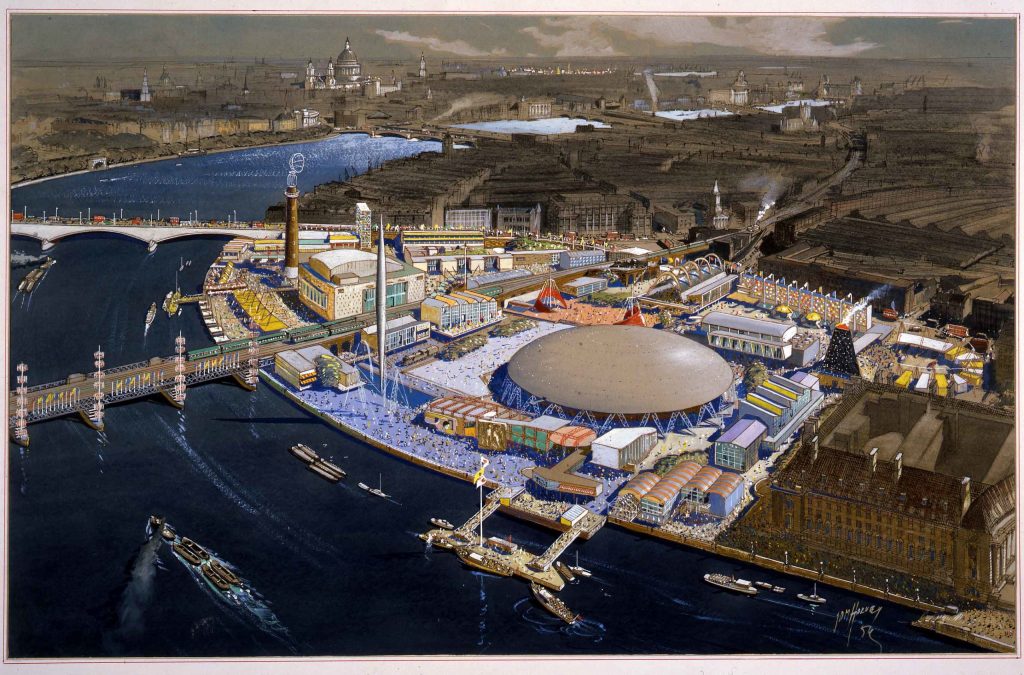

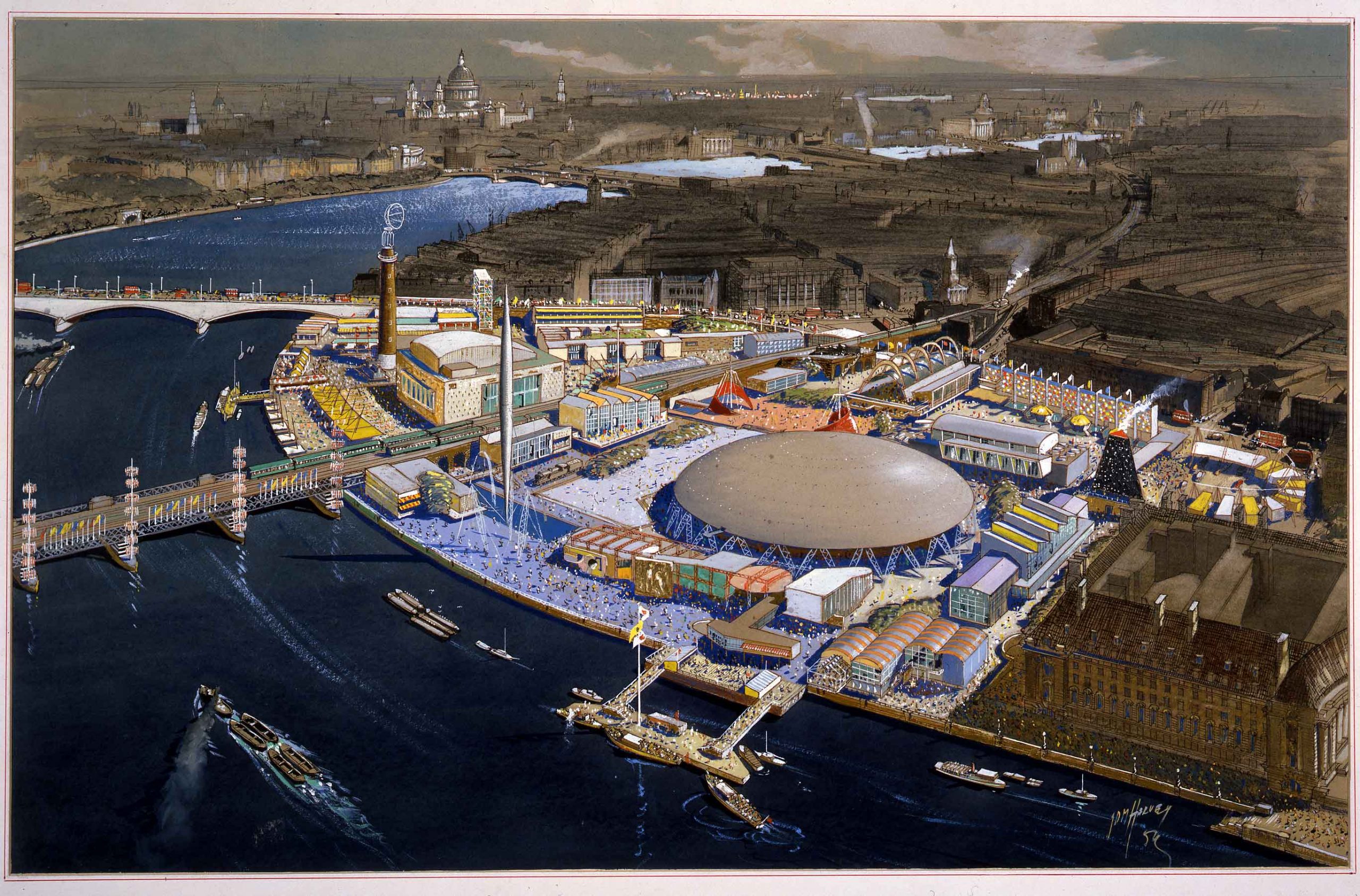

Artist’s view of the Festival on London’s South BankThe Festival of Britain has certainly earned some interesting and pithy descriptions in the sixty-five years since it was staged. In the words of its Director-General, Gerald Barry, it represented “a tonic to the nation” after twenty years in which Britons had successively endured economic depression, total warfare and acute post-war austerity.1 In the case of Winston Churchill, however, several historians have claimed that he saw the Festival in a very different and darker light. In particular, various commentators have alleged that Churchill (then Leader of the Opposition) was vehemently opposed to the venture and regarded it as “three-dimensional socialist propaganda.”2

Artist’s view of the Festival on London’s South BankThe Festival of Britain has certainly earned some interesting and pithy descriptions in the sixty-five years since it was staged. In the words of its Director-General, Gerald Barry, it represented “a tonic to the nation” after twenty years in which Britons had successively endured economic depression, total warfare and acute post-war austerity.1 In the case of Winston Churchill, however, several historians have claimed that he saw the Festival in a very different and darker light. In particular, various commentators have alleged that Churchill (then Leader of the Opposition) was vehemently opposed to the venture and regarded it as “three-dimensional socialist propaganda.”2

2024 International Churchill Conference

While this dramatic phrase has been used repeatedly, it is equally striking that it has never been properly sourced. As a result, it is surely high time to consider whether Churchill was as hostile to the Festival as this alleged comment suggests and a number of historians have asserted. Alternatively, does any firmer evidence exist to show that his stance towards the project was actually conciliatory or even supportive, in sharp contrast to the historical consensus that has developed since the Festival took place?

Expected Antagonism?

It would be understandable if Churchill had been every bit as antagonistic to the venture as so many previous accounts have suggested. In terms of its personnel, for example, the Festival of Britain (inspired by the centenary of 1851’s Great Exhibition) could have hardly have been more provocative to the once and future Prime Minister. Above all, perhaps, Churchill often held the then Lord President and main Festival Minister, Herbert Morrison, in particularly low esteem, especially after “Lord Festival” (as he was nicknamed) had blamed Churchill for a wartime disaster in his Lewisham constituency, agitated for an early end to his wartime coalition, and then questioned his right to draw a salary as Leader of the Opposition when, after 1945, other commitments often kept him away from Westminster.

In similar vein, the project’s Director-General had hardly been chosen with a view to securing Churchill’s enthusiastic backing for the Festival. On the contrary, Churchill had long been antagonised by Gerald Barry during the latter’s spell as editor of the News Chronicle, not least during the Second World War.

Some of Barry’s day-to-day decision-making as Director-General can be seen as just as provocative as his newspaper’s written words. For example, the Festival logo was designed by Abram Games, who had produced a famous health-themed wartime poster (“Your Britain. Fight for It Now”) which Churchill described as “a disgraceful libel on the conditions prevailing in Great Britain before the war.”3 Similarly, Barry’s appointee as the Festival’s architecture director, Hugh Casson, had been a wartime activist in the Commonwealth Party, which Churchill regarded as irresponsible for contesting by-elections while the conflict was ongoing. In his view, such polls were “completely out of keeping with the gravity of the times,” when “the future of our country and, indeed, of all civilisation is in the melting pot.”4

Myth and Reality

In such circumstances, it is easy to appreciate why so many historians have argued or assumed that Churchill was profoundly hostile to the Festival from its official inception (in December 1947) to its formal closure (in September 1951) and even beyond. Indeed, as several of their works have pointed out, the Festival’s centrepiece site (on London’s South Bank) was largely demolished during Churchill’s peacetime premiership, which began within a month of the Festival ending.

Other writers have contended that Churchill’s hostility was less protracted, but no less intense, by suggesting that his previously “vituperative criticisms” of the project were either reduced or even ended by the appointment (in March 1948) of his close friend and wartime chief-of-staff, Lord “Pug” Ismay, as Chairman of the Festival Council.5 However, each of these arguments needs to be reassessed in the light of four sets of evidence, which show or suggest that Churchill was far less antagonistic towards the Festival than previous accounts have argued or implied.

First, Churchill’s political record indicates that he tended to support, rather than oppose, the concept of Britain staging major national and international celebrations. As long ago as 1921, as Colonial Secretary, he had been heavily involved in planning the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley, which took place three years later. On its closure, moreover, Churchill led the way in arguing (successfully) that it should be reopened in 1925: as he wrote to Stanley Baldwin, the then Prime Minister, another season would be “like having a second brew of tea out of the same pot.”6 More recently, while serving in 10 Downing Street himself, Churchill had been content for London to replace Helsinki as the venue for the 1948 Olympic Games, which proved to be enormously successful (despite Britain’s ongoing economic austerity). Opposing the Festival would, therefore, have been a departure from previous practice as far as Churchill was concerned.

Secondly and more substantively, a simple examination of Churchill’s comments in Parliament shows that he was generally silent on the Festival before and after Ismay’s appointment to its supervisory Council, confounding the oft-repeated suggestion that “Pug” had been appointed in order to end the supposed stream of criticisms from his close friend and former political master. In reality, Churchill had long been silent on the subject already and was happy to let the relevant Labour Ministers be “shadowed” by reasonably senior Conservative colleagues. As they did so, their comments included Walter Elliot (a former Scottish Secretary) welcoming the original announcement about the Festival as “a good proposal” and “a worthy object,” while, in the House of Lords, Lord Tweedsmuir wished the project “Godspeed” from the Opposition frontbench.7

Such comments hardly suggest that either the Conservatives in general or Churchill, as the party’s leader, were “dead against” the Festival, as Casson later claimed and successive studies have accepted.8 Indeed, when Churchill himself finally spoke on the subject, in October 1950, his words were also positive in nature. As he explained in a debate on the King’s Speech (before being interrupted by a Labour backbencher): “We are going to have a Festival of Britain next year in which both Parties will take part. We shall do our best to help the Government to make the Festival a success….”9

Such supportive words even prompted Labour Prime Minister, Clement Attlee to propose that they undertake a joint visit to the South Bank to show that the Government and the Opposition were equally committed to the Festival’s success. As Attlee concluded, “The value of such a visit would be very great.”10 It was a suggestion that Churchill willingly accepted although the initiative (planned for early December 1950) proceeded to be overtaken by events when Attlee headed, instead, to the United States for urgent discussions with President Truman about the deepening Korean War.

Parliamentary records also provide the third (and most conclusive) set of evidence to show that Churchill and the Conservatives were far more sympathetic towards the Festival of Britain than has previously been understood. In short, four pieces of enabling legislation were necessary to allow the Festival to be staged and, as the Official Report shows, each received unqualified Conservative support. Indeed, all four Bills were allowed to pass “on the nod” (in other words, without a vote) in both the Commons and the Lords. While such support has been ignored in a whole range of recent studies, it attracted considerable comment at the time in publications ranging from the New York Times (whose readers were informed that Churchill’s “opposition party tacitly has supported the Government’s plans”) to some campaign literature produced by the Labour Party itself, which conceded that Conservative “leaders have all along supported the Festival.”11

Parliamentary records also provide the third (and most conclusive) set of evidence to show that Churchill and the Conservatives were far more sympathetic towards the Festival of Britain than has previously been understood. In short, four pieces of enabling legislation were necessary to allow the Festival to be staged and, as the Official Report shows, each received unqualified Conservative support. Indeed, all four Bills were allowed to pass “on the nod” (in other words, without a vote) in both the Commons and the Lords. While such support has been ignored in a whole range of recent studies, it attracted considerable comment at the time in publications ranging from the New York Times (whose readers were informed that Churchill’s “opposition party tacitly has supported the Government’s plans”) to some campaign literature produced by the Labour Party itself, which conceded that Conservative “leaders have all along supported the Festival.”11

Fourthly and finally, it is noticeable that Churchill became an active contributor to the Festival as its public opening drew near. The displays on the South Bank included both a corrected proof of his Memoirs of the Second World War (on which Ismay had worked as a key adviser) and a valuable cigarette box, which Festival organisers were allowed to borrow after offering (as one of them put it) “the firmest assurances of safety… against a firm conviction by Sir Winston that he would not see it again,” which, embarrassingly, he did not.12 Away from the South Bank, Churchill even entered his best racehorse, Colonist II, in a celebratory race meeting (the Festival of Britain Stakes) at Ascot.

Not Unequivocal

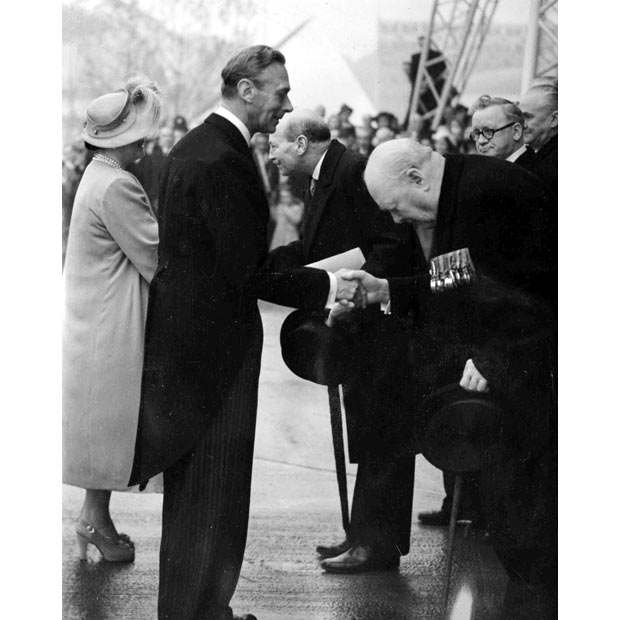

Yet despite his actions as a racehorse owner, a contributor to the South Bank’s exhibitions, and (above all) as a party leader, the Festival of Britain did not receive Churchill’s unequivocal support. In late 1950, for example, he voted against plans to allow the Festival Pleasure Gardens’ funfair to open on Sundays (which Morrison favoured to help balance the project’s books, but Churchill opposed on moral grounds) and, early the next year, he privately expressed “increasing doubts” about Britain staging a national festival while the international situation was so bleak.13 In the event, though, his support was never withdrawn, and he gave every impression of enjoying the South Bank’s formal opening in early May. It certainly appears to have introduced him to escalators and, in the process, provided the elder statesman with plenty of child-like entertainment and delight. According to David Kynaston, the distinguished British historian, Churchill had always been “a taxi rather than a Tube man” and proceeded to ride the escalators repeatedly in preference to seeing the Festival’s actual exhibits!14

Just as previous accounts have claimed that Churchill “loathed” the Festival as Leader of the Opposition, it has also been suggested, repeatedly, that his dislike of the project was so intense that he behaved vindictively towards the South Bank after returning as Prime Minister in the wake of the General Election in October 1951.15 For instance, John Tusa has referred to the “vengeful despoliation of the site” under the Conservatives, Lesley Gillilan has criticised the “churlish” conduct by Churchill and his Ministers, and Mary Banham claimed that almost every exhibition building was “smashed and carted away the day after the Festival closed—an act of vandalism claimed to have been ordered by Churchill” himself.16

Such claims have contributed to the perception of Churchill leading a new government, which was philistine in nature, vindictive towards its inheritance from Attlee’s administration, and far keener to stage an essentially backward-looking Coronation (in 1953) than to preserve the futuristic architecture of so many Festival buildings. As a result, the historical reputation of Churchill’s peacetime premiership has been tarnished by his perceived approach to the Festival and its physical legacy, especially its iconic architectural symbol, the “Skylon.”

Again, however, the evidence points in a rather different direction and contradicts the portrait painted collectively by Hillier, Gillilan, and Tusa. For example, not only did the Festival close in the last few weeks of the Labour Government, rather than in the early days of its Conservative successor, but contemporary accounts confirm that bulldozers had moved onto the South Bank well before Churchill moved back into Downing Street. Similarly, the archives of the London County Council (which was then Labour-controlled) reveal that its leaders were keen for the South Bank to be cleared as soon as possible so that the site’s long-term redevelopment could get underway.

Finally, an abundance of evidence shows that the various exhibition buildings, with the sole exception of the Royal Festival Hall, had been designed to last for the five months of the Festival but not beyond, with Casson even welcoming their “impermanence” (in a 1950 lecture) on the basis that it encouraged “an uninhibited even playful approach to design.”17 Many were consequently demolished under Churchill’s premiership but hardly on his orders or for spiteful political reasons, as so many previous accounts have suggested.

A Second Brew of Tea

Indeed, Churchill’s entirely pragmatic approach to the whole project is perhaps best demonstrated by the case of the Festival Pleasure Gardens, in Battersea. Far from calling for their demolition, Churchill approved plans for the Gardens’ re-opening in 1952, a move which increased the Festival’s legacy and was expected (wrongly) to reduce the enormous debts which had been accumulated, largely due to chronic mismanagement, during their construction. It was hardly an example of Churchill regarding the Festival as “three-dimensional socialist propaganda.” It was, more prosaically, his latest attempt to get “a second brew” from the same pot of tea.

Endnotes

1. Daily Mail Festival of Britain Preview and Guide, undated, p. 3.

2. For example, Sue MacGregor, Festival Times, Festival of Britain Society, Edition 50, autumn 2003, p. 9.

3. See John Allan, Berthold Lubetkin: Architecture and the Tradition of Progress (London: RIBA Publications, 1993), p. 442.

4. Paul Rusiecki, “The Maldon By-Election of 1942,” The Historian, Edition 114, Summer 2013, pp. 22–26.

5. Adrian Forty, “Festival Politics” (pp. 26–38), in Mary Banham and Bevis Hillier, eds. A Tonic to the Nation: The Festival of Britain, 1951 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1976), p. 29.

6. Winston Churchill to Stanley Baldwin, 9 November 1924, CHUR 18/2, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge.

7. Official Report (Commons), 5 December 1947, Volume 445, cols. 692–93; Official Report (Lords), Volume 161, 10 March 1949, Cols. 282 and 284.

8. Quoted by Nicholas Ind, Terence Conran: The Authorized Biography (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1995), p. 55.

9. Official Report (Commons), Volume 480, 31 October 1950, Col. 16.

10. Attlee to Churchill, 10 November 1950, CHUR 2/96B, Churchill Archives.

11. New York Times, 20 November 1950; Notes for Speakers: New Year Campaign 1951, Labour Party, London, 1951, pp. 6–7.

12. George Backhouse, “Organizing the Festival,” Banham and Hillier, p. 162.

13. Winston Churchill to Sir Anthony Eden, January 1951 (precise date unclear), Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Volume VIII, Never Despair, 1945–1965 (London: Heinemann, 1988), p. 583.

14. David Kynaston, Family Britain, 1951–57 (London: Bloomsbury, 2009), p. 6.

15. Bevis Hillier, The Spectator, 18 June 2011.

16. John Tusa, The Observer, 17 June 2007; Lesley Gillilan, The Observer, 15 April 2001.

17. Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Volume 57, April 1950, p. 212.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.