Finest Hour 177

Books Arts & Curiosities – A Matter of Pride

November 7, 2017

Finest Hour 177, Summer 2017

Page 52

Review by John Campbell

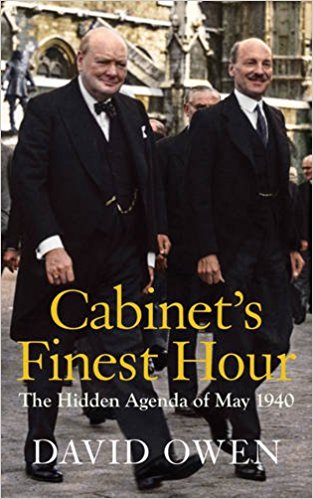

David Owen, Cabinet’s Finest Hour: The Hidden Agenda of May 1940, Haus Publishing, 2016, 276 pages, £18.99.

ISBN 978–1910376553

It has become quite a trend for senior British politicians in their retirement to turn to writing history. Following the example of Roy Jenkins, Cabinet veterans Douglas Hurd, William Hague, Roy Hattersley, and others have produced books of some distinction. Some years ago David Owen— Foreign Secretary for two years in the 1970s, but a neurologist before entering politics—brought his medical training to bear in an interesting and original book entitled In Sickness and in Power examining the effect of ill health, usually covered up, on heads of government over the past hundred years, ranging from Churchill and Roosevelt through Anthony Eden and John F. Kennedy to George W. Bush and Tony Blair. In the last two cases he diagnosed, in relation to the Iraq war, a condition he called “Hubris Syndrome,” which he has been trying to popularise ever since. His latest book, disguised as history, is in reality a renewal of his indictment of Blair by means of a clumsily-constructed revisiting of the discussion of possible peace terms in Churchill’s War Cabinet in May 1940.

The ostensible starting-point of the book is that Churchill, in writing his history of the war, glossed over these discussions by asserting that “the supreme question of whether we should fight on alone never found a place on the War Cabinet agenda.” Though literally true, this was, as has long been recognised, seriously misleading, since the six-man War Cabinet did in fact, over nine meetings in three days between 26 and 28 May, wrestle with the question of how to respond to the proposal of Paul Reynaud, the French Prime Minister, to ask Mussolini to broker some sort of peace settlement before France collapsed, leaving Hitler free to launch the invasion of Britain. Churchill was determined not to be dragged down any such slippery slope but to fight on alone; but his position as a new Prime Minister widely mistrusted by much of his own Conservative party was precarious. Lord Halifax, as Foreign Secretary, was still anxious to explore every possible opening to end the war, and Neville Chamberlain, Churchill’s predecessor who still commanded strong support, was inclined the same way. The balance was swung by the two Labour members, Clement Attlee and his little-remembered deputy, Arthur Greenwood, who played a crucial role, and the Liberal leader, Archibald Sinclair—an old friend whom Churchill shrewdly added to the War Cabinet in the confidence that he would support him. But the outcome was not pre-ordained. Until the “miracle” of Dunkirk managed to bring back most of the British army from France, the military outlook was dire, and the air superiority needed to prevent a German invasion doubtful. Yet Churchill skilfully prised Chamberlain away from Halifax and with the support of Attlee, Greenwood, and Sinclair carried the day to the extent that he could later pretend that it had never been in question: “We were much too busy to waste time on such unreal, academic issues.”

There is nothing new in this. Owen’s re-telling leans heavily on Roy Jenkins’s 2001 biography of Churchill. Owen’s point in re-hashing it is to assert that Britain’s “Finest Hour,” in Churchill’s phrase, was also the Cabinet’s finest hour and a vindication of coalition government, properly conducted. At the heart of his book Owen reprints (in the original typescript for added authenticity) the minutes of the nine tense War Cabinet meetings which record the sway of arguments alongside some of the diplomatic memoranda and military reports on which the ministers had to base their decision. The cautious bureaucratic language of the official documents—which includes the chilling assessment that “Germany has ample forces to invade and occupy this country. Should the enemy succeed in establishing a force, with its vehicles firmly ashore, the Army in the United Kingdom, which is very short of equipment, has not got the offensive power to drive it out”—does vividly convey the desperate situation they faced. Churchill’s heroic defiance shines through, but so too does his care to bring his colleagues with him.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Then in a final chapter, Owen reveals his real purpose, which is to contrast Churchill’s scrupulous following of correct constitutional procedure, even at this moment of mortal national danger, with Anthony Eden’s drug-distorted handling of the Suez crisis, Margaret Thatcher’s increasing neglect of Cabinet and Parliament, and above all Blair’s reckless by-passing of Cabinet and abuse of intelligence to commit the country to war in Iraq—all examples of Owen’s “Hubris Syndrome.” “No British Prime Minister in wartime,” he writes, “not Asquith, Lloyd George, Churchill or even Eden…made strategic decisions as Blair did over Iraq, personally and without systematically involving senior Cabinet colleagues.” The wilful destruction of Cabinet government was “a hubristic act of vandalism for which, as Prime Minister, Blair alone bears responsibility,” and the war “a saga of hubristic incompetence,” which should constitute an impeachable offence. It is time, Owen concludes hopefully, “to reconsider Presidential Prime Ministerships and revert under Theresa May to a Cabinet Office structure which for a century served us well.” Thus the example of May 1940 is called in aid to point a lesson for today.

John Campbell’s books include major biographies of F. E. Smith, Aneurin Bevan, Edward Heath, Margaret Thatcher, and Roy Jenkins.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.